Selected Criticism

Lowery Stokes Sims, 1984

Essay from the catalog, Graham Modern Gallery, New York

For Carmen Cicero, it has been a long patient wait for the rest of the world to catch up with him. He is not alone. One can think of several other artists—including Philip Guston—who left abstraction in the late 60s and began doing a “funky” figuration that is so much in vogue these days, and who were ridiculed until the art world finally modified its exclusively formalist point of view.

The body of works exhibited at Graham Modern have come out of the last nine years or so. They were executed after Cicero’s studio and all its contents were completely destroyed by fire in 1971. While this catastrophe would stump the critic or the art historian, it certainly does not mean that the artist does not continue and start anew, often with startling results, as seen in the case of Alfred Leslie, who went through a similar experience. These works are not discontinuous with Cicero’s works of the 1950s and 60s. Reminiscences of the earlier, gestural figural style can be observed and one can discern the persistence of an underlying cubist structure. And, characteristic of a generation of artists who were influenced by Hans Hofmann’s inimitable way of transmitting modernist ideas, the work contains a sense of formal punning and references. The tactile, visceral surfaces that he shared with such contemporaries as Leon Golub, have also survived in the recent paintings, effecting a nice bridge to the work of the current generation of figurative artists.

The new work is replete with a touch of wry wit that veers toward, but never quite becomes, hostility. It is that type of humor we are accustomed to calling “biting.” It is also combative and rebellious, and defiant in its unrepentant exposure of the raw emotion that lies just beneath the veneer of civilization. This point of view has certainly been shaped by Cicero’s long-time residence on the Bowery, where he migrated after the fire and the collapse of his personal life. The transition there from a more conventional and comfortable life in the suburbs to what was then the frontier of the downtown art world, certainly shaped the sardonic fatalism of his work which has only recently begun to be modified. One of the best examples can be seen in “Death Hails a Cab” where death is seen on the piers in the early morning hailing a taxi. It is a completely contemporary allegory in its deadpan approach to devastation. It makes sense that the apocalyptic forces would not necessarily come on horseback in a blaze of light in this age. Hoses are obsolete and star war movies have made us blasé of light in this age. Now, it is much more sinister when the destroyer mills among us, unknown, doing its work piecemeal, letting us drop off one by one quietly. And then, like a Dracula, it will flee the early morning light by what else? A cab.

While Cicero will attribute the macabre, visionary and surreal aspects in his work to the haunting vision of a Ryder, and, dare we suggest, a Blake or Fuseli, for me is the sly devious humor of James Thurber that is called to mind in encountering Cicero’s compositions. Perhaps it is because Cicero’s subjects include the cast of characters in the most enduring battle of all times—that between the sexes, and he depicts them in a variety of interactions: love, hate, lust, violence and above all drama. But like Thurber’s indomitable adversaries, Cicero’s are always equal in the fray. There are no victims, no underdogs. This factor is all the more interesting because, like any male of his generation, Cicero’s feelings on the contemporary situation between men and women are contradictory. He may be put off by the current female prototypes, which are quite different from those he knew growing up, but he can’t help but persist in finding salvation in the same women he fears. The narratives in these works can be seen as allegories for situations he has been in, various states of mind, and above all as vehicles for him to work out all these feelings. His incurable romanticism comes out in a composition such as Flying Down to Rio where he mimics the worst kind of sentimentality and cliché, complete with the hot, nubile woman rushing base breasted to the cool, smoldering Latin-type under the palm trees and tropical moon. Don Ameche, Casar Romero, Rossano Brazzi where are you?

But—lest we be side-tracked by the subject matter—let us note that the same compositions are amazingly complex and rigorous in terms of their spatial organization. The contours of his figures become not only a means t delineate shapes, but spatial devices that establish visually what the relationships will be to the shape next to it. This is all the more provocative because one can see painted space but have it denied by what is actually happening visually or coloristically.

Cicero also does collages that have a direct relationship to those formal concerns. He considers the collages complete when they have some of the qualities that direct the imagery of prevailing atmosphere…they look slightly apparitional…the color is somewhat dreamlike…” As he does with his paintings, he works on several collages at a time. He assembles the different compositions simultaneously.

The ordering of the geometric shapes in the collages is similar to the shapes and interstices that are evident in the paintings. Cicero is able to explore the actual nature of the relationship between the shapes of the figural works in the collages. As he changes the placement of the color shapes in each collage, he observes how the atmosphere and the local color also changes, and how the intensity of the color is modified in its relative replacement, and in its coexistence with another set of colors and shapes. It is not unlike the color experiments of Josef Albers.

Cicero’s drawings, on the other hand, are done strictly on impulse, and indicate the early states of the paintings. Their peculiar animation and energy become in the paintings an underlying, exploratory linearity. Randomly searching and moving, he begins to draw, scribbling on the canvas. As he has noted, he then waits until he is in an “intense mood” be it happy or sad, so long as the emotion is strong.

Then he begins to paint, and hopes that his subconscious material will begin to reveal itself out of the meandering framework he has set up. This method reminds one of a combination of a Zen Buddhist watercolor master and a surrealist automatist. Like the surrealist whose uses “frottage,” he meditates on the unguided scribblings to see the imagery, to find it out of the maze.

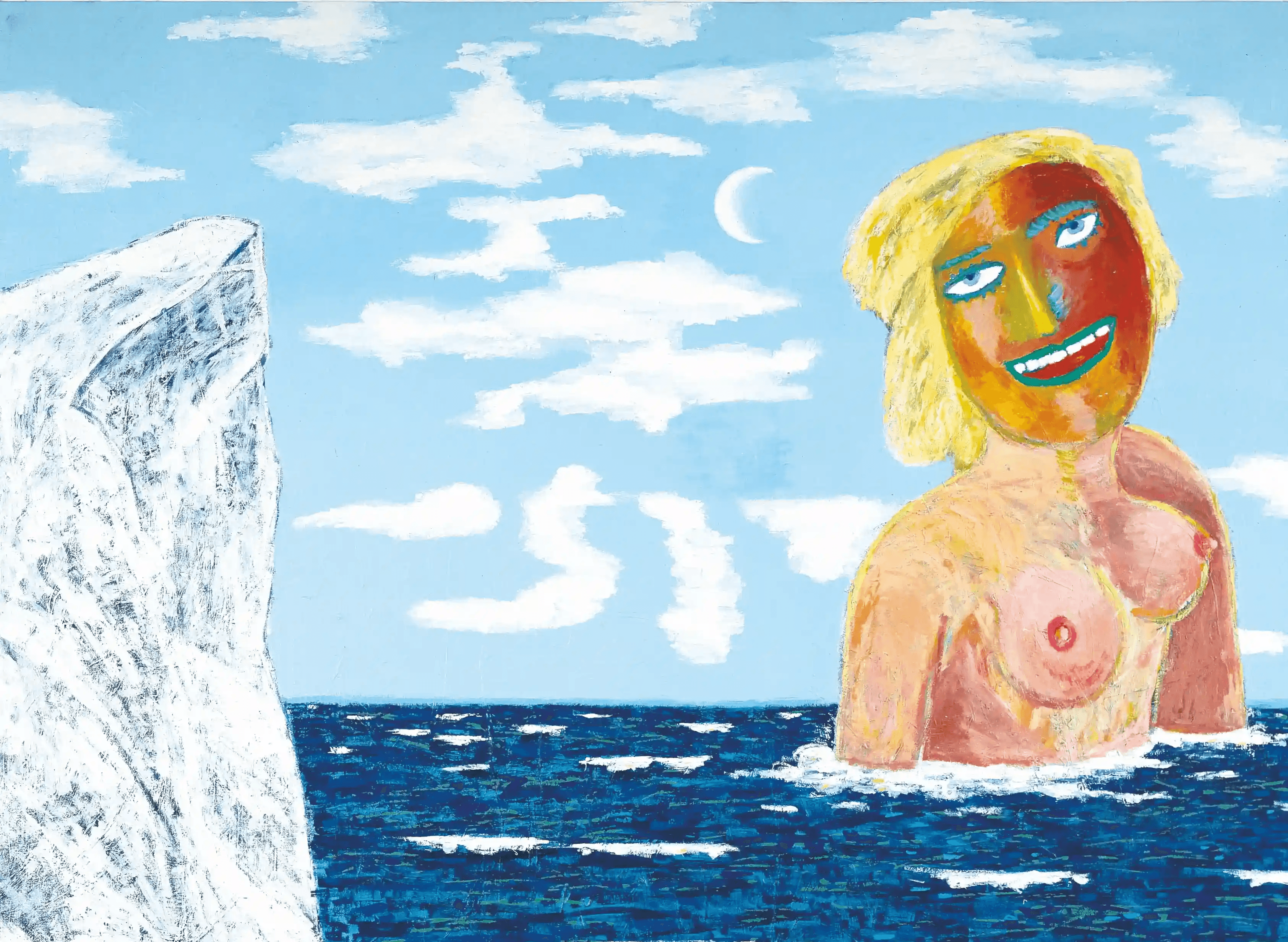

The cartoon quality of the paintings makes them seem so casual, and this belies the obsessive process that Cicero brings to each work, the care with which he places each color and shape, seeking in that process to maintain a certain freshness. For instance, he uses color not merely to depict light but also as light itself. In Provincetown Princess he searched tirelessly for the right tonalities for the sky and the water, painting and repainting that area of the composition. He finally took a clue from the observation of a friend who reminded him that in Provincetown one experiences a warm sun, but at the same time the air remains cool. The rosy blondness that he achieved in the gargantuan bather only serves to enhance our empathetic experience of that blue in the painting. We cannot help but conjure the work of Milton Avery who was also painting in the same area, and indeed Cicero achieves a play on perspective and flatness in his composition that would have been appreciated by Avery.

I mentioned earlier that in spite of the currency of the “look” of Cicero’s work that his is not to be confused with the philosophical and formal foundations of the newer generation of figural artists. Above all Cicero is mired in his generation, and he proceeds out of the influence of Avery and Hofmann and their particular translation of Matisse and Picasso. Cicero’s mythologies are also grounded in his youth. His persona is the tough hipster of the beat generation, an imagery culled from figures as varied as James Dean, Jack Kerouac, and even Norman Mailer. For this reason, his work has an especial interest to us in this time and place.

Donald Kuspit, 2000

“Carmen Cicero: Fantasist,” from the catalog Carmen Cicero Paintings: a Survey, exhibition catalog, Provincetown Art Association and Museum

If “phantasy activity, being rooted in the instincts, is…their mental corollary,” as the psychoanalyst Melanie Klein writes, then Carmen Cicero’s fantastic images are raw with instinct. It first appears, barely tamed by form, in his abstract expressionist paintings. It is evident in their stark rather forceful lines and the interplay of black and white, emblematic of the conflict between the life and death instincts—a primitive, ceaseless drama which, as Klein says, is implicated in every fantasy. There is a primordial immediacy and emotional majesty to Cicero’s abstractions, confirming their expressive depth. Abstraction, 1954, is an explosive flurry of spontaneous brushstrokes, while Near Tibidabo, 1958, and Odradek, 1959, are bizarre constructions of lines. In The Kiss, 1955, line becomes outline, demarking odd structures, at odds with one another, and in Untitled, 1955, quick lines and painterly marks interact in a strangely shaped void.

All these “instinctive” works seem subliminally figurative, as though their energy was being channeled into a form not yet familiar enough to be named as human but still bodily enough to be experienced as human in principle, however grotesque the body may seem. It certainly looks grotesque in Untitled, while Near Tibidabo and Odredek can be read as bizarre conflations of body parts, horrifically mangled and compressed by fantasy. Is it a crucifixion or orgy—mating of animal and human?—we are witnessing, however abstracted, distorted, flattened? They are masterpieces of ambiguity, indeed, linear tours de force, in which horror vacui—the surrounding black emptiness—is almost filled with the innerving if morbid lines. There seem to be more normal—less nightmarish—figures in Abstraction and The Kiss (the upper half of a male figure in the former, the lower half of a female figure in the latter?), but they remain elusive inferences rather than firm representations. There is an air of tragic urgency about Cicero’s abstract expressions, but the actors in the drama are less evident than its bleakness. Suffering is furiously conveyed, but it has no human context.

That context is supplied in the sixties, when Cicero turned to figuration. The tortured ambivalence of Cicero’s abstract works now has a human setting. Again and again Cicero pictures human conflict—figures in conflict with one another, whether that conflict takes sexual or more broadly social form. He in effect embeds the life and death instincts in human form, imaginatively objectifying their conflict in violent fantasies.

The man and woman in The Exit of E-5, 1962, are not as obviously at war as the man and woman in the Battle of the Sexes, 1972, but their relationship is not exactly harmonious. The man faces away from the woman, looking at a kind of mapa mundi: an enigmatic abstract painting, implicitly that of the inner cosmos—a primordial landscape, its horizon separating a murky orange sky and a clear blue ocean, spotted with eccentrically shaped black islands—as the halos of bright color that frame it suggest. The man is facing a choice between the spiritual work of art and the flesh and blood woman. The choice is also conveyed by the difference between the upper half of the picture, plunged in darkness, and the yellow lower half, where the bright colors of the concentric rings repeat in rectangular form. The circular and rectangular structures have more coherence than the flattened figures, overlaid with networks of lines that suggest the lines of their bodies. These figures, at once expressionistic and cubist in style, are also divided between dark and light areas. The woman is more black than white, the man more white—and blue, the color of the sky and thus a symbol of spirituality. He is presumably a higher being than she is. But he is also clearly at odds with himself. He is self-estranged, as well as alienated from the woman. She also is divided against herself, and far from comfortable with the man. The sharp contrasts that pervade the pictures—not only those of light and dark, but also of curve and angle—convey its inner violence, that is, its unresolved contradictions.

Cicero explores existential themes, but he does so in a peculiarly lighthearted, humorous way. His wild figures are abstract cartoons: the awkwardness of their construction—a very carefully calculated awkwardness—makes them more amusing than terrifying. They are comically discombobulated forms—incoherent to the point of grotesqueness yet ironically droll—that seem more improvised than substantial. If, as Baudelaire said, the grotesque—the freakish—is the comic at its most absolute, then Cicero’s figures are absolutely hilarious, for he has given the grotesque an uncanny new human form, or else brought out the inherent freakishness of human beings in a vivid new way. The cartoon hero of Mr. Ghost Goes to Town, 1982, makes the point clearly, all the more so because the whiteness of his face suggests both the comic mask of the clown and the tragic nakedness of the skull. Humor takes away the bitter edge of this grim figure, and makes him even more original.

Humor is a mature defense against the instincts, as Freud said, and Cicero’s absurd figures are funny enough to make us laugh at the violence of their instincts, even as we are forced to take it seriously. Nowhere is the tangle of life and death instincts—sexuality and death—more fiercely displayed than in the weird Battle of the Sexes, 1972, and Crime, 1976. Each figure in these tragicomic masterpieces is what Freud called “a cauldron full of seething excitations”—“a chaos” of instincts and primary process. At the same time, the figures, fantasies of virility—tortured virility and sexuality—are comic ghosts. The man and woman in the Battle of the Sexes dissolve into gestural anarchy, while the aggressive figure that personifies Crime seems like a mirage in the gestural whirlpool that surrounds him. These intense, vibrant, truly “sensational”—sensation-full—works convey a sense of relentless drive and conflict, inner and with the world. One can’t help wondering if the blue “rope” in which the figure in Crime is tied up or entangled—it forms his contour—is a symbol of social restraint or self-restraint. His crime seems to be no more than his expression of his sexual and aggressive instincts. He is raw instinct in tentative human form, unable to contain the energy of the instincts he “binds.” The figures in the Battle of the Sexes and Crime make no effort to be civilized, that is, to inhibit themselves for the sake of peace and safety. There is no suppression or sublimation of instinct in Cicero’s figurative paintings, only its expression in a figurative form as raw as itself.

The manic surge of instinct seems to have disappeared in Prince Charming, 1981—the figures are more composed, geometrically coherent (although they also have a deceptively improvised, hastily thrown together look)—but the death instinct has not. One figure is about to stab the other figure in the back, which is why death stands between them. As in the Battle of the Sexes and Crime, no reason for the conflict is suggested, as it was in The Exit of E-5, where it involved the choice between art and sex. The violence is instinctive—given by nature. The same irrational point is made in Battle of the Sexes II, 1992. Gestural wildness has disappeared, but the war between man and woman continues unabated, and both remain split personalities. Each has a dapper, physically attractive light side and a dark, grotesque primitive side. But a split personality does not mean a divided will, for both the troglodyte and the dandy, the beauty and the shadowy beast within her, are willfully violent. Even the attractive Provincetown Princess, 1984, is a split personality, for the iceberg or stone mountain in the foreground represents her inner coldness or hardness of heart. And her conceited funny face belies her beauty. Neither the opposites on the inside or the outside unite in Cicero’s paintings, although the painfulness of their relationship is mitigated by the humor of their representation. Cicero is an artist god laughing at the antics of his creations, however much they may be projections of the conflict within himself—the nightmare which the self is, as Nightmare, 1985, suggests. This grotesque, painted, split personality is also haunted by woman, as the upside down female face attached to his left leg, like a ball and chain, suggests.

The setting of Nightmare, is a lonely desert, and while the desert disappears in Cicero’s works of the nineties, the loneliness remains. These works are painted with a remarkably meticulous touch. Cicero has always been concerned with detail, but now he is more obsessed than ever and the detail more minute. Instead of broad strokes, wild gestures, and eccentric geometry we have carefully managed touch informing a carefully staged scene. Instead of improvisation, we have a clearly rendered, carefully crafted work, which seems to have been thought out beforehand. Instead of looseness—a sense of let the paint fall where it may—we have concentration and deliberateness. We have full consciousness, rather than unconscious accident—ego control rather than painterly parapraxis. The setting remains bizarre and fantastic, if more bright and familiar than the nightmare setting of the pervious works. What seems to me crucial is that instead of two figures in conflict, or one erotically aggressive figure, Cicero presents a single figure isolated in a landscape. The violence has gone. The question is, what remains?

Magritte’s Hat, 1999, floats in a rather dreamy, idyllic landscape—a picture postcard perfect nature. In Saain Takes a Holiday, 1999, a man parks his convertible in a similar, if darker landscape—it seems to be sunset, and there are rocks on the country road and along one side of it. In another work a small airplane flies through a forest of giant, dead trees, following a stream with stones that seem to make a path. The shadows are long and dense for all the bright moonlight. In Going Home, 1999, a figure—is it Mr. Ghost, dressed in the black of death?—walks alone on a sidewalk made of slabs of stone. An old stone wall is behind him, and behind it are two factory buildings that also seem made of stone. The peculiarly archaic, old-fashioned scene is completely gray, except for the fragments of green that flank the factory buildings, and the black sky, lightened by the factory smoke and clouds, which are almost indistinguishable. We are on the edge of town, and leaving it. The Bookkeeper, 1998, is also a night scene. The car the bookkeeper drives is pitch black, the road unpaved, the trees on one side of it seem dead. Lacking outside lights, the bookkeeper keeps the inside lights on, as he better do, not only to see, but to feel alive. It is clearly later than he thinks, and he may have lost his way. Like all the other figures, he has been humbled by circumstances beyond his control.

But Christ Appears in Ohio, 1999, is all light and color, as befits the occasion of the Resurrection. The figure of Christ is borrowed from Grünewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece, the clouds are yellow streaks of incandescent light, the green all but overwhelming. Abandoned gesture has turned to careful stippling, and an isolated country house confirms the pastoral privacy of the setting. We are in heaven, in principle if not in fact. In the marvelous Green River, 1992-99, Cicero pictures heaven on earth: fertile green water flows through a desolate, stony landscape, bringing the pine trees to vibrant life. Some have been cut down, but more will always remain. Light emanates from the green trees, forming a kind of protective aura around them. They stand out against the violet gray, their radiant green subliminally in harmony with the radiant yellow of the sky. Life will be renewed despite death. The dry river bed will again flow with the water of life, turning the desert into a garden of paradise.

What are Cicero’s new fantasies about? His paintings have lost their expressionistic fierceness and become surreal dreamscapes. They are hallucinatory and focused rather than reckless, emotionally and physically. And, as I have said, they are no longer focused on relationships, but on the self, sometimes in symbolic form (hat, car, airplane). Satan takes a holiday, death walks by, and the resurrected Christ appears: it is a narrative of the self waiting for death, aware of death, in the presence of death, and hoping for the best—for salvation. Anticipating death, Satan repents, the bookkeeper is terrified, the car seems lost in the wilderness, the airplane looks small in the dark forest of depression, as Dante called it, in the valley of the shadow of death, as the Old Testament calls it. The path of life—the country road, the stream, and finally, in the Christ picture, a footpath—leads to death and, hopefully, to salvation—to heaven, where the grass is always green. Why wouldn’t Christ appear in a meadow in Ohio, if heaven is a meadow, in which the season is always spring or summer, as Jan van Eyck suggested in the Ghent Altarpiece? If Satan turns to Christ, then we know the season has changed. Mr. Ghost—Death—has come to town, but Christ lives in the countryside. The “folksy,” clumsy look of Cicero’s new work—the image of Christ looks as though it was clipped from an illustration and copied by a folk artist or child—is deceptive. It puts a coat of humor on the skeleton of eschatology. Cicero keeps his good humor in the face of death—a noble attitude, much preferable to stoicism. The heroics of the abstract expressionist paintings have been replaced by the heroism of the individual alone with death, and heroically defying it with humor.

It is a remarkable career: from dead serious abstract paintings, fraught with existential drama—the self enacting its deepest emotions in the arena of the painting, as Harold Rosenberg called it—through tragicomic images of human relationships at their most raw, and back to the existential drama of the self, now facing the end of its life with good humor. Good humor is rare enough, but so is an authentic sense of tragedy, with or without color. Carmen Cicero’s works have been appreciated for their wit and humor, but not for their seriousness—their existential earnestness, insight, and courage—and visual sophistication. They tell the story of his journey through life with a charm that belies their conviction.

Robert Berlind, 2007

“Cicero’s Mysteries,” from the catalog Carmen Cicero Watercolors: Things That Happen in The Moonlight, June Kelly Gallery, New York

A man in trench coat and fedora is seen hurrying through Carmen Cicero’s moonlit world. He strides; more than that, he epitomizes striding, as though driven either by some urgent need or in perpetual flight from some peril. Whichever the case—the circumstance is unclear—he hurries to no apparent avail. He, we, are stuck, dreamlike, in some never-to-be-resolved drama. We know him from recent acrylic on canvas paintings such as The Red Shoes of 1999-2000, The Great Mountain, 2003, The Ruisdael Enigma, 2004, and we find him in recent watercolors as well, some of them reworkings of the larger paintings.

When not on foot he may drive (A Truro Road) or fly (unseen in the airplane of Flying Low) and in one notable instance without a plane (Duchamp Flies). We know this man from somewhere: our dreams perhaps or any number of fictions involving misdeeds and mystery, maybe a film noir of the Forties. As with all dream life, we come, on reflection, to recognize the dreamed man as the one who dreams, which is to say, the viewer as well as the artist. Cicero’s sensibility is not hermetic; he does not deliberately obscure his subjective projection. This harried figure is a familiar persona, one that we know from countless narratives, popular and literary, and, as is the case with most protagonists, he is one’s own anxiously questing self.

The landscape, the ground across which this figure moves, is also strangely familiar: a country road or wooded site that may call to mind Hopper’s or Frost’s often ominous rural America or Dante’s mid life selva oscura. A Bachelardian poetics animates the toy-like cars, trains, boats and planes that have figured in Cicero’s work from early on. We might be reminded of Charron’s ferry, the Little Engine that Could, Maurice Sendak’s boats and planes, or Philip Guston’s funky, fugitive cars. One imagines these vehicles as instruments not only of transportation but also as possible agents of transformation from one realm to another.

The sites and figures of Cicero’s narratives derive both from his own Cape Cod and Manhattan surroundings and from art of the past. He may quote directly from Botticelli, Ruisdael, Rembrandt, Velázquez, or De Chirico, but these instances are not a matter of appropriation. That is, they do not presume control of the masterworks to which they refer but, instead, attest to their habitation and shared psychological resonances in our collective consciousness. Castle Hill Road could have been conceived by Hopper but for the blue person approaching from the right, a monochromatic figure of a different order from the rest of the picture and of a divergent scale, so that he looms like one of De Chirico’s statues. Princess depicts a sumptuously outfitted figure out of 17th Century Spain who seems as astonished as we are to find herself in leafless nocturnal woods.

There are literary sources as well, for example in Scene from a Joseph Conrad Story, with its derelict bark drifting in toward a menacingly dark shore. Here the absence of the figure is, in itself, poignant, accentuating the emptiness of the little boat and, the possibly unseen inhabitants of the dark forest.

Almost always some narrative is in progress. Prince Valley Road depicts a running man clad only in tattered pants anxiously looking behind him as he flees across a dark path. Painted in grisaille, he is illogically illuminated by more than the moon that hovers overhead in the gap between bare branches. The awkwardness of his anatomy and the bright, spectral light that models his body give him the feel of a character from a local folk tale or a Washington Irving story.

Certain of Cicero’s images are more enigmatic still. Castle of Otranto focuses on an exotic red-breasted bird perched upon a white rock projecting from a pond with the castle far in the distance. The Barn features a brightly colored bird and moth, both exquisite and strange, against a dark site with the barn of the title a dark presence to the left. In Night Music, a comical large bird standing on the ground listens attentively to Rousseau’s silhouetted flute player. The combination of the inky dark of the figure and the woods, the clear colors of the bird, and the bright snow-covered ground and pale sky recall Magritte’s Empire of Light with its paradoxical vision of conjoined night and day. Such incongruities may elicit quiet wonder, often after a surprised laugh at being taken unawares. Intimation of mortality, the sort that filter through dreams and lurk within all of the arts, are the ghosts in these pictorial machines.

Cicero has traveled a great distance since making his stark black and white abstractions (or near-abstractions) of the 50’s and the expressionist figurative paintings that he produced through the 80’s. These rough images link him with such contrarians as George McNeil, Leon Golub, Robert Colescott, and the late Philip Guston, all of whom contested the cool posture of various mainstreams through the late 20th Century. Two large acrylic on canvas paintings entitled Battle of the Sexes, 1972, and Battle of the Sexes II, done twenty years later, evince a no-holds-barred improvisatory process that propels their obstreperous images.

With the advent of the 90’s the paintings become less expressionist (not to say any less expressive) and more visionary. Cicero’s world is now brought forth not so much through a hard-fought agon of picture making (that legacy of the Abstract Expressionist mythos) as it is fully envisioned and, it would seem, innocently transcribed. If these paintings bear a resemblance to illustrations in children’s books, this is because their fanciful imagery precedes the process of painting more than growing out of it. Their character does indeed derive from how they are painted—their palette, their spatial construction, their particular attention to detail—but one now feels that their facture is in the service of an otherworldly reality. In this Cicero’s visionary paintings are also like much so-called outsider art: humble transcriptions in which the artist’s first obligation is fidelity to the received image.

Contrary to the common notion that watercolor depends either upon panache of execution or the timid modesty of a genteel hobby, Cicero builds his paintings deliberately, step by step, layering dense textures, and even repainting networks of tiny marks where he feels the need to accentuate or modify a particular passage. Each stroke is a focused move within what comes to seem a devotional process, as though to assure the enduring stability of a fleetingly glimpsed apparition. Using opaque watercolors (gouache) he is able to lay light marks on top of dark ones and to make whatever corrections he chooses. He deftly and unpredictably plays this technique off against atmospheric transparencies as in the fluidly painted sky of Castle Hill Road. Here the moon is rendered by the white paper, while in other paintings such as Venezia (into which the clown out of an early Hopper has been unaccountably transported) the moon and its aura are rendered with opaque white against the dark sky. What counts is the darkly luminous, oneiric image to which these techniques contribute.

Jasper Johns famously characterized his subject matter as “things the mind already knows,” Cicero might say the same, although he would be referring to another part of the mind: not that mental file furnished with its catalog of received, habitual formations (a target, a map, stenciled numbers) but a realm where deeper, archetypal narratives are in play. For all their surreal quirkiness we encounter Cicero’s mysterious pictures as if returning to some site in a dream we have dreamt countless times before.