Music

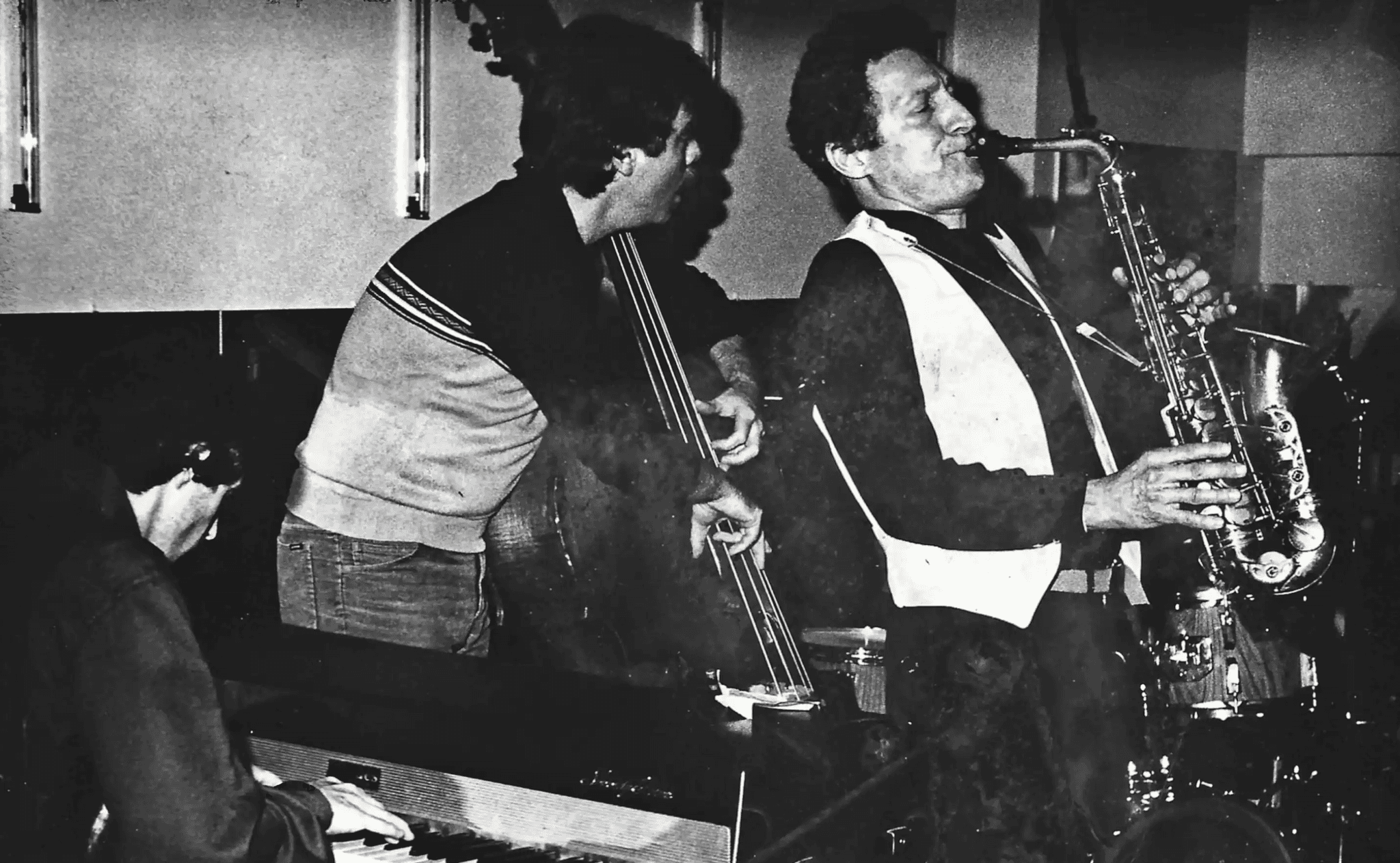

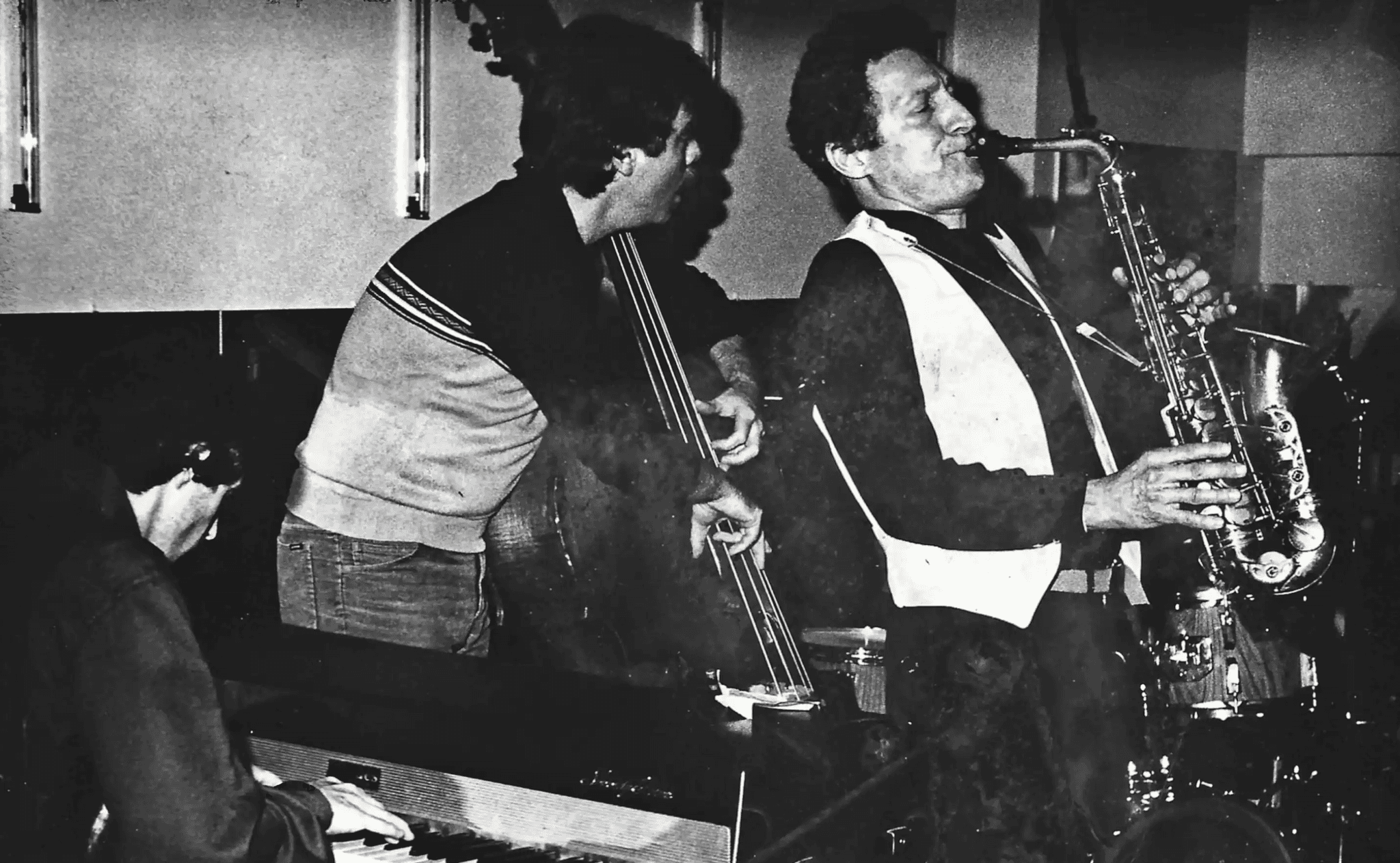

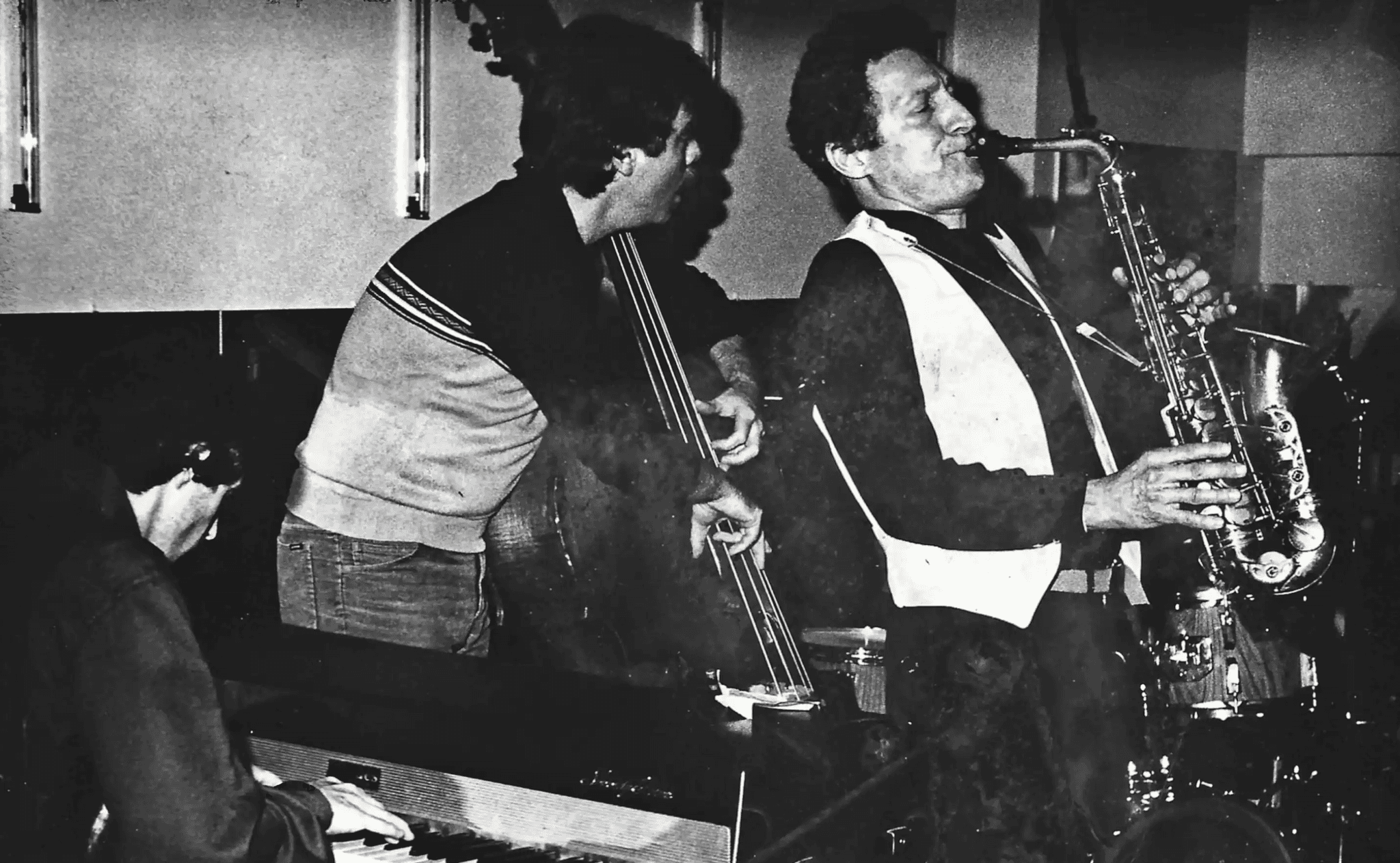

Kent Hewitt, Carmen Cicero and Ron McClure playing in a club in the Lower East Side, New York, 1982.

Carmen Cicero and Music

Cicero’s early musical training on the clarinet began conventionally in elementary school where he was classically trained—chromatic scales and such and quickly distinguished himself by mastering the classic Flight of the Bumblebee. An enthusiastic and dedicated student, Cicero enjoyed practicing and set his sights on a musical career, playing in the school band and orchestra. Among his early teachers was Charles Thetford, who played first chair clarinet in the Radio City Music Hall Orchestra. Cicero became first clarinet chair in the New Jersey All-State Orchestra and was a member of a pep band dressed in uniforms that played at baseball games. He became interested in jazz after listening to the big bands. Cicero’s next professional teacher was Joe Allard, the

Cicero’s early musical training on the clarinet began conventionally in elementary school where he was classically trained—chromatic scales and such and quickly distinguished himself by mastering the classic Flight of the Bumblebee. An enthusiastic and dedicated student, Cicero enjoyed practicing and set his sights on a musical career, playing in the school band and orchestra. Among his early teachers was Charles Thetford, who played first chair clarinet in the Radio City Music Hall Orchestra. Cicero became first clarinet chair in the New Jersey All-State Orchestra and was a member of a pep band dressed in uniforms that played at baseball games. He became interested in jazz after listening to the big bands. Cicero’s next professional teacher was Joe Allard, the legendary saxophonist and clarinetist who played

Cicero’s early musical training on the clarinet began conventionally in elementary school where he was classically trained—chromatic scales and such and quickly distinguished himself by mastering the classic Flight of the Bumblebee. An enthusiastic and dedicated student, Cicero enjoyed practicing and set his sights on a musical career, playing in the school band and orchestra.

Among his early teachers was Charles Thetford, who played first chair clarinet in the Radio City Music Hall Orchestra. Cicero became first clarinet chair in the New Jersey All-State Orchestra and was a member of a pep band dressed in uniforms that played at baseball games. He became interested in jazz after listening to the big bands. Cicero’s next professional teacher was Joe Allard, the legendary saxophonist and clarinetist who played with Toscanini and taught many great clarinet and sax players. For his favorite students, Allard would go to the Buffet Clarinet Factory in Paris, where he was well known by the proprietors, and allowed to select the finest instruments for his students. So, his pupil, Cicero, was the fortunate recipient of what he called his “Stradivarius” clarinet. He began playing weekends with a commercial trio providing music for countless bar mitzvahs, weddings and parties. Cicero then expanded his professional pursuits by playing with bands in the “Borsht Belt”—the famous Jewish summer resorts in the Catskills of upstate New York.

The band was always a mix of ethnicities—Jews, Italians, Poles and more and the only judgments passed were along musical lines. In addition to being an accomplished clarinet player, Cicero picked up the saxophone and also played drums on some jobs. “We had a hell of a good time,” Cicero recalls, “most of us were footloose young guys and we enjoyed meeting other musicians and playing together on and off stage. It was a wonderful way to spend a summer. The money wasn’t great but the food was and besides, we didn’t have many expenses. We’d bunk together, sometimes four to a room but that was all right we were having fun.”

Cicero’s early musical training on the clarinet began conventionally in elementary school where he was classically trained—chromatic scales and such and quickly distinguished himself by mastering the classic Flight of the Bumblebee. An enthusiastic and dedicated student, Cicero enjoyed practicing and set his sights on a musical career, playing in the school band and orchestra.

Among his early teachers was Charles Thetford, who played first chair clarinet in the Radio City Music Hall Orchestra. Cicero became first clarinet chair in the New Jersey All-State Orchestra and was a member of a pep band dressed in uniforms that played at baseball games. He became interested in jazz after listening to the big bands. Cicero’s next professional teacher was Joe Allard, the legendary saxophonist and clarinetist who played with Toscanini and taught many great clarinet and sax players. For his favorite students, Allard would go to the Buffet Clarinet Factory in Paris, where he was well known by the proprietors, and allowed to select the finest instruments for his students. So, his pupil, Cicero, was the fortunate recipient of what he called his “Stradivarius” clarinet. He began playing weekends with a commercial trio providing music for countless bar mitzvahs, weddings and parties. Cicero then expanded his professional pursuits by playing with bands in the “Borsht Belt”—the famous Jewish summer resorts in the Catskills of upstate New York.

The band was always a mix of ethnicities—Jews, Italians, Poles and more and the only judgments passed were along musical lines. In addition to being an accomplished clarinet player, Cicero picked up the saxophone and also played drums on some jobs. “We had a hell of a good time,” Cicero recalls, “most of us were footloose young guys and we enjoyed meeting other musicians and playing together on and off stage. It was a wonderful way to spend a summer. The money wasn’t great but the food was and besides, we didn’t have many expenses. We’d bunk together, sometimes four to a room but that was all right we were having fun.”

legendary saxophonist and clarinetist who played with Toscanini and taught many great clarinet and sax players. For his favorite students, Allard would go to the Buffet Clarinet Factory in Paris, where he was well known by the proprietors, and allowed to select the finest instruments for his students. So, his pupil, Cicero, was the fortunate recipient of what he called his “Stradivarius” clarinet. He began playing weekends with a commercial trio providing music for countless bar mitzvahs, weddings and parties. Cicero then expanded his professional pursuits by playing with bands in the “Borsht Belt”—the famous Jewish summer resorts in the Catskills of upstate New York. The band was always a mix of ethnicities—Jews, Italians, Poles and more and the only judgments passed were along musical

with Toscanini and taught many great clarinet and sax players. For his favorite students, Allard would go to the Buffet Clarinet Factory in Paris, where he was well known by the proprietors, and allowed to select the finest instruments for his students. So, his pupil, Cicero, was the fortunate recipient of what he called his “Stradivarius” clarinet. He began playing weekends with a commercial trio providing music for countless bar mitzvahs, weddings and parties. Cicero then expanded his professional pursuits by playing with bands in the “Borsht Belt”—the famous Jewish summer resorts in the Catskills of upstate New York. The band was always a mix of ethnicities—Jews, Italians, Poles and more and the only judgments passed were along musical

lines. In addition to being an accomplished clarinet player, Cicero picked up the saxophone and also played drums on some jobs. “We had a hell of a good time,” Cicero recalls, “most of us were footloose young guys and we enjoyed meeting other musicians and playing together on and off stage. It was a wonderful way to spend a summer. The money wasn’t great but the food was and besides, we didn’t have many expenses. We’d bunk together, sometimes four to a room but that was all right we were having fun.”

“Carmen and I would create good music with imagination, wit, and even humor and allow anything to happen. I began to see the authentic spirit of artistic creation develop and how as musicians we were pursuing the same explorations of creativity and dynamism between man and nature as were the painters.” - Kent Hewitt

L-R: Mike Melillo, piano; Carmen Cicero, alto saxophone; Roy Cumming, bass; Glenn Davis, drums; c. 1971

L-R: Mike Melillo, piano; Carmen Cicero, alto saxophone; Roy Cumming, bass; Glenn Davis, drums; c. 1971

L-R: Mike Melillo, piano; Carmen Cicero, alto saxophone; Roy Cumming, bass; Glenn Davis, drums; c. 1971

Cicero was drafted into the Army during World War II and with his musical résumé became the leader of a 16-piece band that entertained the troops at Camp John Hay near the city of Baguio in the Philippines. After the war, although he was proficient in a wide variety of musical styles—from classical orchestral music through jazz and the American songbook to show tunes and even a little country, blues and rock and roll—Cicero preferred a jazz style that was so new and so innovative that it hadn’t even been named yet. It is now called “free form.” As an Abstract Expressionist and Figurative Expressionist painter, Cicero was working with a wholly new vocabulary of visual expression and it is natural that his creative work in music would take the

Cicero’s early musical training on the clarinet began conventionally in elementary school where he was classically trained—chromatic scales and such and quickly distinguished himself by mastering the classic Flight of the Bumblebee. An enthusiastic and dedicated student, Cicero enjoyed practicing and set his sights on a musical career, playing in the school band and orchestra. Among his early teachers was Charles Thetford, who played first chair clarinet in the Radio City Music Hall Orchestra. Cicero became first clarinet chair in the New Jersey All-State Orchestra and was a member of a pep band dressed in uniforms that played at baseball games. He became interested in jazz after listening to the big bands. Cicero’s next professional teacher was Joe Allard, the legendary saxophonist and clarinetist who played

Cicero was drafted into the Army during World War II and with his musical résumé became the leader of a 16-piece band that entertained the troops at Camp John Hay near the city of Baguio in the Philippines. After the war, although he was proficient in a wide variety of musical styles—from classical orchestral music through jazz and the American songbook to show tunes and even a little country, blues and rock and roll—Cicero preferred a jazz style that was so new and so innovative that it hadn’t even been named yet. It is now called “free form.” As an Abstract Expressionist and Figurative Expressionist painter, Cicero was working with a wholly new vocabulary of visual expression and it is natural that his creative work in music would take the new road, too. Cicero formed a trio with a couple of top-flight musicians, Vinnie Burke (bass) and Al Senurchio (saxophone). They honed their distinct “free form” style. This innovative, improvisational, free association style of playing is now a unique genre in the jazz canon. There might have been other musicians in the world exploring this style but Cicero and his friends didn’t know about it. And neither did DOWNBEAT magazine.

The trio played college concerts and a lot of private parties and also made the jazz club scene in New York City. It was at one of these jobs that a photographer from DOWNBEAT captured these musicians in action and put them in the pantheon of progressive jazz. Cicero also played free form music with Mike Melillo (piano), who worked with Sonny Rollins, Phil Woods and Harry Leahey; Glenn Davis (drums) who was with the renowned pianist Marian McPartland’s group for extended periods; and Roy Cumming (bass) who was a regular with Harry Leahey (guitar) along with other outstanding jazz musicians.

The jazz pianist Kent Hewitt, who played in bands and recording sessions with such jazz greats like Kenny Burrell and Pepper Adams, met Cicero in Provincetown in 1978 and the two began playing together both on Cape Cod and in New York at some of the artist’s jazz parties.

Cicero was drafted into the Army during World War II and with his musical résumé became the leader of a 16-piece band that entertained the troops at Camp John Hay near the city of Baguio in the Philippines. After the war, although he was proficient in a wide variety of musical styles—from classical orchestral music through jazz and the American songbook to show tunes and even a little country, blues and rock and roll—Cicero preferred a jazz style that was so new and so innovative that it hadn’t even been named yet. It is now called “free form.” As an Abstract Expressionist and Figurative Expressionist painter, Cicero was working with a wholly new vocabulary of visual expression and it is natural that his creative work in music would take the new road, too. Cicero formed a trio with a couple of top-flight musicians, Vinnie Burke (bass) and Al Senurchio (saxophone). They honed their distinct “free form” style. This innovative, improvisational, free association style of playing is now a unique genre in the jazz canon. There might have been other musicians in the world exploring this style but Cicero and his friends didn’t know about it. And neither did DOWNBEAT magazine.

The trio played college concerts and a lot of private parties and also made the jazz club scene in New York City. It was at one of these jobs that a photographer from DOWNBEAT captured these musicians in action and put them in the pantheon of progressive jazz. Cicero also played free form music with Mike Melillo (piano), who worked with Sonny Rollins, Phil Woods and Harry Leahey; Glenn Davis (drums) who was with the renowned pianist Marian McPartland’s group for extended periods; and Roy Cumming (bass) who was a regular with Harry Leahey (guitar) along with other outstanding jazz musicians.

The jazz pianist Kent Hewitt, who played in bands and recording sessions with such jazz greats like Kenny Burrell and Pepper Adams, met Cicero in Provincetown in 1978 and the two began playing together both on Cape Cod and in New York at some of the artist’s jazz parties.

new road, too. Cicero formed a trio with a couple of top-flight musicians, Vinnie Burke (bass) and Al Senurchio (saxophone). They honed their distinct “free form” style. This innovative, improvisational, free association style of playing is now a unique genre in the jazz canon. There might have been other musicians in the world exploring this style but Cicero and his friends didn’t know about it. And neither did DOWNBEAT magazine. The trio played college concerts and a lot of private parties and also made the jazz club scene in New York City. It was at one of these jobs that a photographer from DOWNBEAT captured these musicians in action and put them in the pantheon of progressive jazz. Cicero also played free form music with Mike Melillo (piano), who worked with

with Toscanini and taught many great clarinet and sax players. For his favorite students, Allard would go to the Buffet Clarinet Factory in Paris, where he was well known by the proprietors, and allowed to select the finest instruments for his students. So, his pupil, Cicero, was the fortunate recipient of what he called his “Stradivarius” clarinet. He began playing weekends with a commercial trio providing music for countless bar mitzvahs, weddings and parties. Cicero then expanded his professional pursuits by playing with bands in the “Borsht Belt”—the famous Jewish summer resorts in the Catskills of upstate New York. The band was always a mix of ethnicities—Jews, Italians, Poles and more and the only judgments passed were along musical

Sonny Rollins, Phil Woods and Harry Leahey; Glenn Davis (drums) who was with the renowned pianist Marian McPartland’s group for extended periods; and Roy Cumming (bass) who was a regular with Harry Leahey (guitar) along with other outstanding jazz musicians.

The jazz pianist Kent Hewitt, who played in bands and recording sessions with such jazz greats like Kenny Burrell and Pepper Adams, met Cicero in Provincetown in 1978 and the two began playing together both on Cape Cod and in New York at some of the artist’s jazz parties.

Trio with Bill Sano (bass), Betty Lee (accordian) and Carmen Cicero (clarinet), 1963.

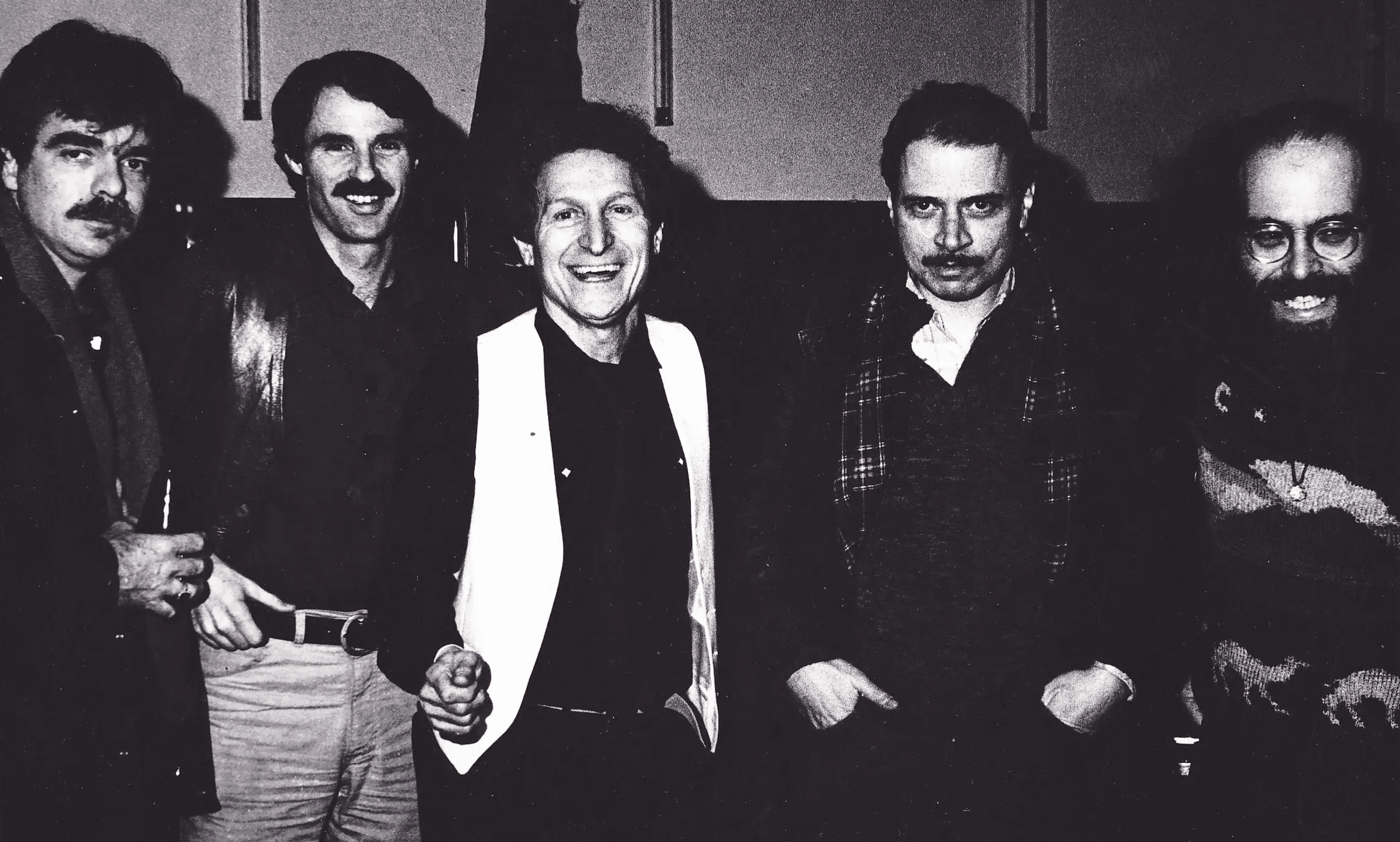

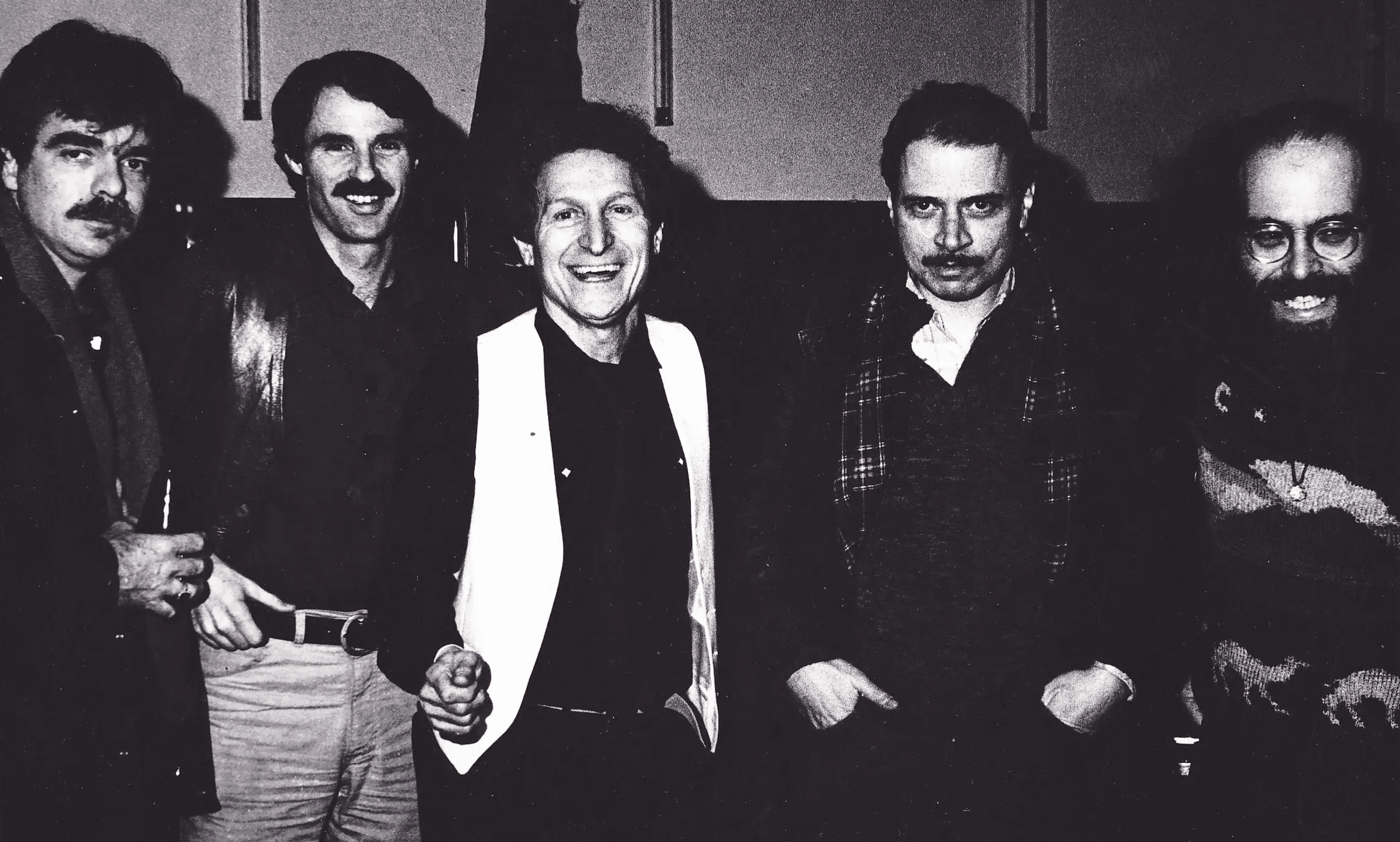

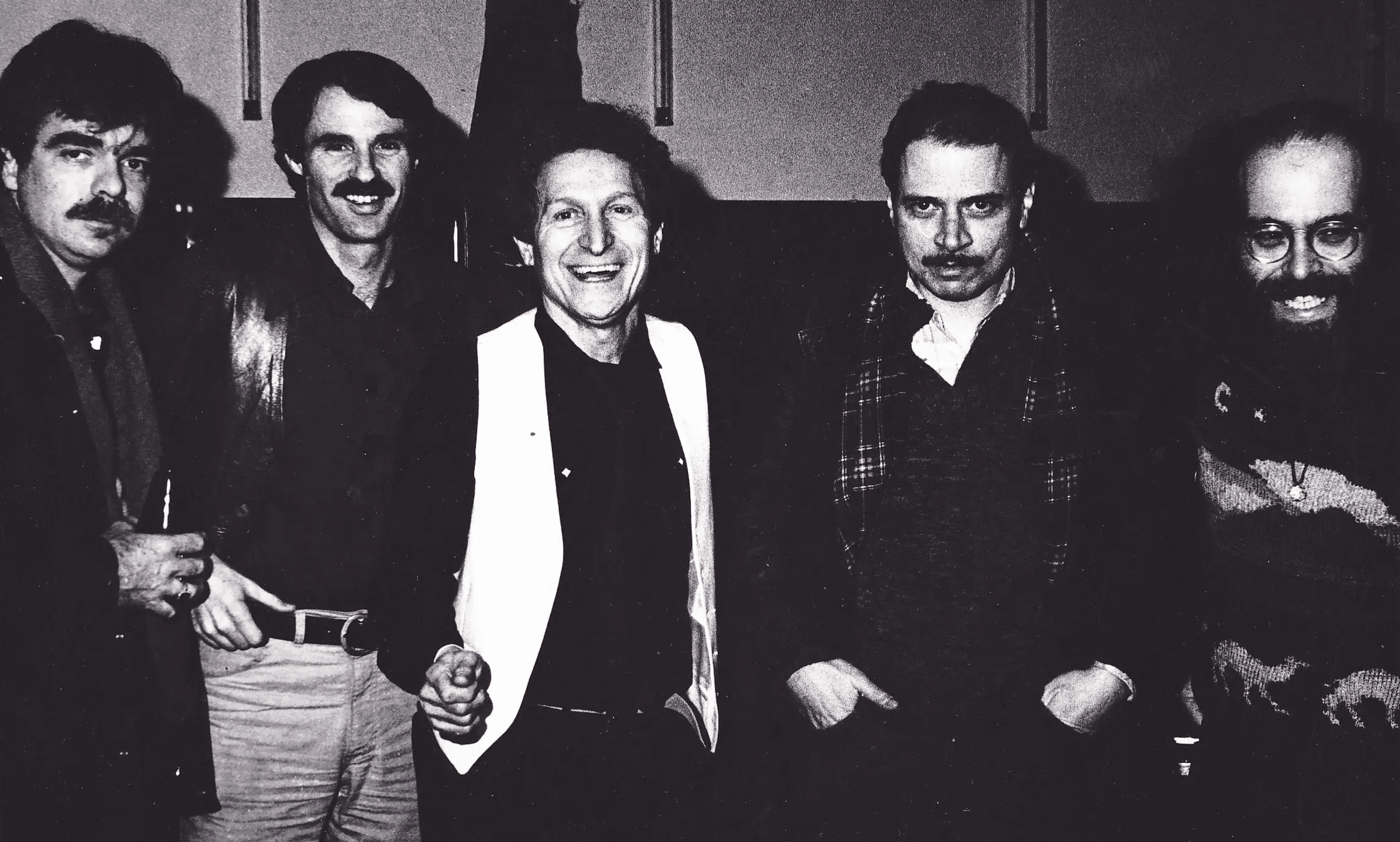

L-R: Ron McClure (bass), Kent Hewitt (piano), Carmen Cicero (sax), Mike Melillo (Piano), Bob Moses (drums). Concert at a restaurant following an art opening on the Lower East Side, Manhattan, 1983.

“It was a most profound experience,” relates Hewitt. “We would create good music with imagination, wit, and even humor and allow anything to happen. I began to see the authentic spirit of artistic creation develop and how as musicians we were pursuing the same explorations of creativity and dynamism between man and nature as were the painters.”

“It was a most profound experience,” relates Hewitt. “We would create good music with imagination, wit, and even humor and allow anything to happen. I began to see the authentic spirit of artistic creation develop and how as musicians we were pursuing the same explorations of creativity and dynamism between man and nature as were the painters.”

The jazz bass player Marshall Wood who worked many years with Tony Bennett was introduced to Cicero by Hewitt and the three began playing during summers on Cape Cod. For 13 years they performed with annually with Bart Weisman (drums) at the Provincetown Art Association and Museum. Marshall has commented that Cicero has “’big ears’—that’s jazz lingo for someone who

Cicero’s early musical training on the clarinet began conventionally in elementary school where he was classically trained—chromatic scales and such and quickly distinguished himself by mastering the classic Flight of the Bumblebee. An enthusiastic and dedicated student, Cicero enjoyed practicing and set his sights on a musical career, playing in the school band and orchestra. Among his early teachers was Charles Thetford, who played first chair clarinet in the Radio City Music Hall Orchestra. Cicero became first clarinet chair in the New Jersey All-State Orchestra and was a member of a pep band dressed in uniforms that played at baseball games. He became interested in jazz after listening to the big bands. Cicero’s next professional teacher was Joe Allard, the legendary saxophonist and clarinetist who played

“It was a most profound experience,” relates Hewitt. “We would create good music with imagination, wit, and even humor and allow anything to happen. I began to see the authentic spirit of artistic creation develop and how as musicians we were pursuing the same explorations of creativity and dynamism between man and nature as were the painters.”

The jazz bass player Marshall Wood who worked many years with Tony Bennett was introduced to Cicero by Hewitt and the three began playing during summers on Cape Cod. For 13 years they performed with annually with Bart Weisman (drums) at the Provincetown Art Association and Museum.

Marshall has commented that Cicero has “’big ears’—that’s jazz lingo for someone who can hear things deep into the music and listens carefully to each musician in the band. And that’s not always the case. Guys with big ears are few and far between but when you find them it’s always a pleasure to play together. I think he loves music as much as he loves painting—they’re the same thing, aren’t they, after all?” Cicero agrees. “Yes, there is a commonality in the arts. For me, art is great when the artist creates that magical atmosphere—a difficult thing to define—one’s consciousness is completely absorbed with the magical spell created by the artist.” Material excerpted from Bill Evaul, “Carmen Cicero: —Musician—The Color of Sound—The Sound of Color.” The Art of Carmen Cicero.

“It was a most profound experience,” relates Hewitt. “We would create good music with imagination, wit, and even humor and allow anything to happen. I began to see the authentic spirit of artistic creation develop and how as musicians we were pursuing the same explorations of creativity and dynamism between man and nature as were the painters.”

The jazz bass player Marshall Wood who worked many years with Tony Bennett was introduced to Cicero by Hewitt and the three began playing during summers on Cape Cod. For 13 years they performed with annually with Bart Weisman (drums) at the Provincetown Art Association and Museum.

Marshall has commented that Cicero has “’big ears’—that’s jazz lingo for someone who can hear things deep into the music and listens carefully to each musician in the band. And that’s not always the case. Guys with big ears are few and far between but when you find them it’s always a pleasure to play together. I think he loves music as much as he loves painting—they’re the same thing, aren’t they, after all?” Cicero agrees. “Yes, there is a commonality in the arts. For me, art is great when the artist creates that magical atmosphere—a difficult thing to define—one’s consciousness is completely absorbed with the magical spell created by the artist.” Material excerpted from Bill Evaul, “Carmen Cicero: —Musician—The Color of Sound—The Sound of Color.” The Art of Carmen Cicero.

can hear things deep into the music and listens carefully to each musician in the band. And that’s not always the case. Guys with big ears are few and far between but when you find them it’s always a pleasure to play together. I think he loves music as much as he loves painting—they’re the same thing, aren’t they, after all?” Cicero agrees. “Yes, there is a commonality in the arts. For me, art is great when the artist creates that magical atmosphere—a difficult thing to define—one’s consciousness is completely absorbed with the magical spell created by the artist.”

Material excerpted from Bill Evaul, “Carmen Cicero: —Musician—The Color of Sound—The Sound of Color.” The Art of Carmen Cicero. Atglen, PA: Schiffer Publishing, Ltd., 2013.

with Toscanini and taught many great clarinet and sax players. For his favorite students, Allard would go to the Buffet Clarinet Factory in Paris, where he was well known by the proprietors, and allowed to select the finest instruments for his students. So, his pupil, Cicero, was the fortunate recipient of what he called his “Stradivarius” clarinet. He began playing weekends with a commercial trio providing music for countless bar mitzvahs, weddings and parties. Cicero then expanded his professional pursuits by playing with bands in the “Borsht Belt”—the famous Jewish summer resorts in the Catskills of upstate New York. The band was always a mix of ethnicities—Jews, Italians, Poles and more and the only judgments passed were along musical

Carmen and his Selmer saxophone in Bowery studio, 1983.

L-R: Carmen Cicero (sax), Marshall Wood (bass), Kent Hewitt (piano), Bart Weisman (drums). 2013.

“Carmen has ‘big ears.’ Of course, that’s jazz lingo for someone who can hear things deep into the music and listens carefully to each musician in the band. And that’s not always the case. Guys with big ears are few and far between but when you find them it’s always a pleasure to play together. I think he loves music as much as he loves painting—they’re the same thing, aren’t they, after all?” - Marshall Wood

Donna Byrne scat singing with Carmen. Provincetown Art Association and Museum, 2014.

Flagship Restaurant, Provincetown, MA, 1993; L-R: Kent Hewitt, Marshall Wood, Carmen Cicero, Glenn Davis. Photograph by Bonnie Shields.

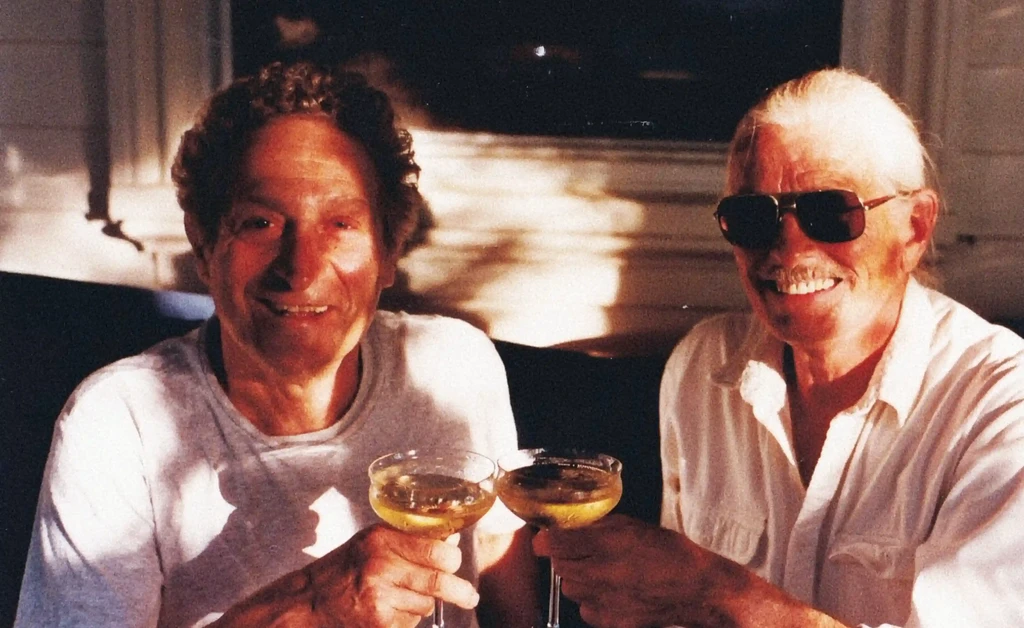

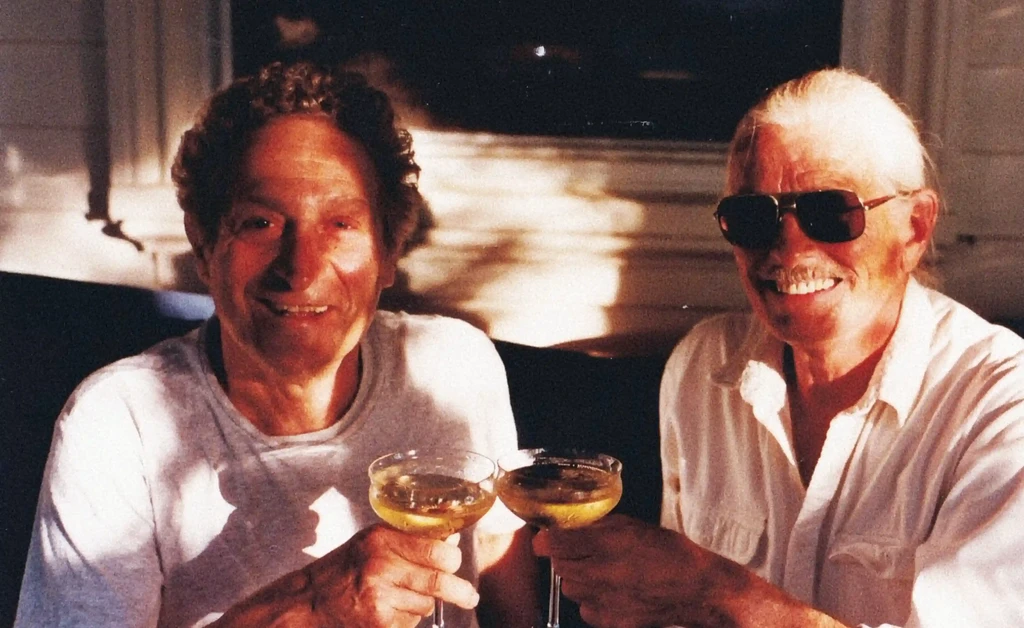

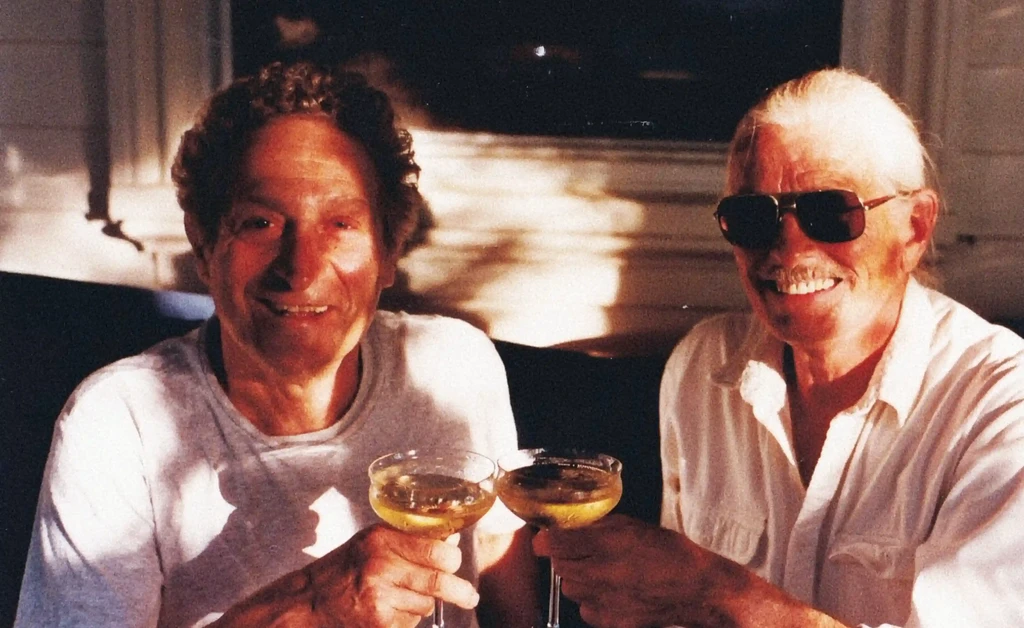

Carmen and George Mueller, Truro, MA, c. 2000. Photograph by Mary Abell.

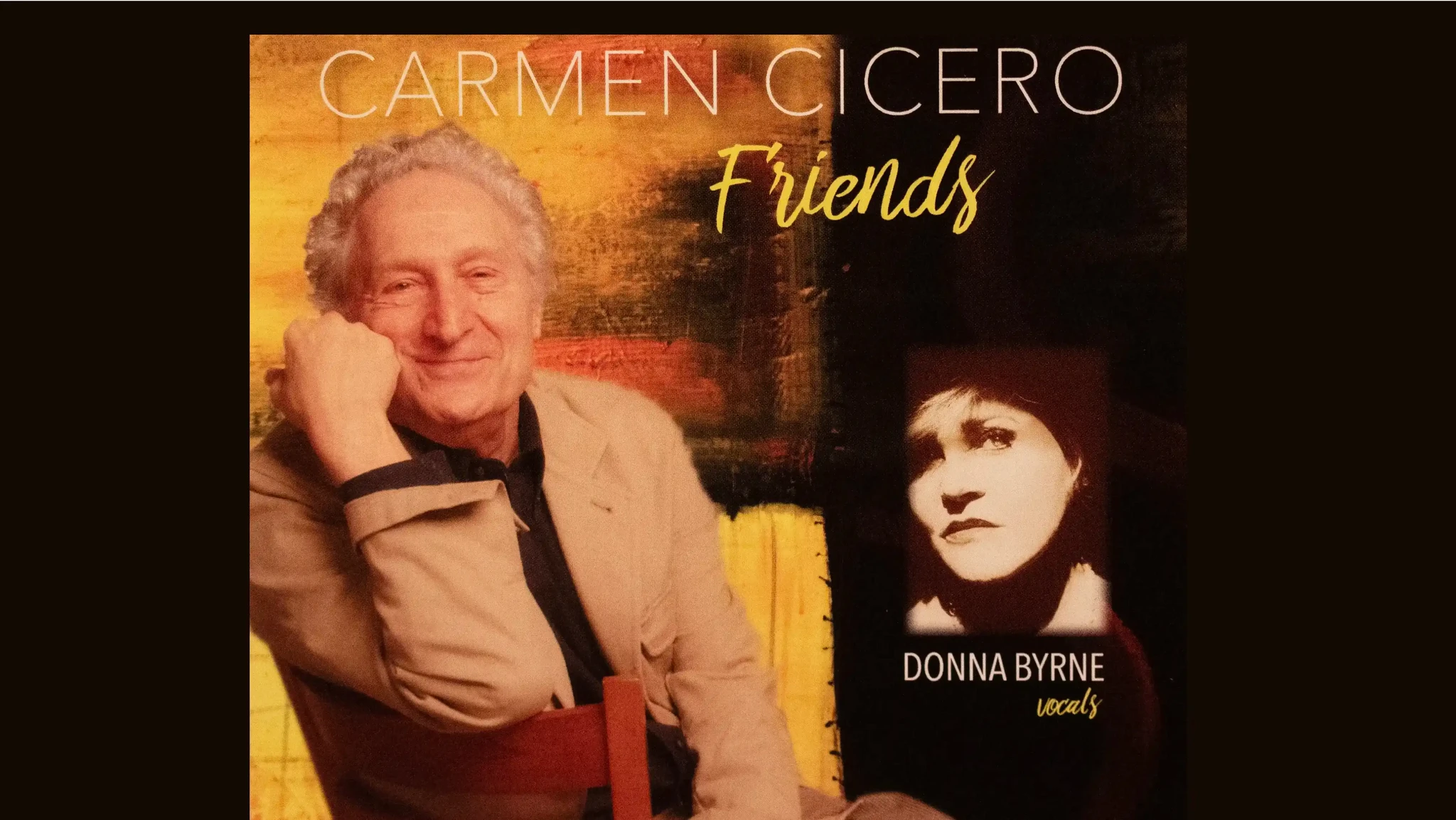

Music CDs

“Music gives you thrills up your spine. Painting does as well, but with music it’s more visceral, particularly if you’re playing it.”

Carmen Cicero, 2023

“Music gives you thrills up your spine. Painting does as well, but with music it’s more visceral, particularly if you’re playing it.”

Carmen Cicero, 2023

“Music gives you thrills up your spine. Painting does as well, but with music it’s more visceral, particularly if you’re playing it.”

Carmen Cicero, 2023

“Music gives you thrills up your spine. Painting does as well, but with music it’s more visceral, particularly if you’re playing it.”

Carmen Cicero, 2023

The contents of this site, including all images and text, are for educational and non-commercial use only and are the sole property of Carmen Cicero. The contents of this site may not be reproduced in any form without written permission from Carmen Cicero. For all image requests and reproduction rights, please contact junekellygallery@earthlink.net.

© 2024 Carmen Cicero. All Rights Reserved. New York City, NY.

Website by

The contents of this site, including all images and text, are for educational and non-commercial use only and are the sole property of Carmen Cicero. The contents of this site may not be reproduced in any form without written permission from Carmen Cicero. For all image requests and reproduction rights, please contact junekellygallery@earthlink.net.

© 2024 Carmen Cicero. All Rights Reserved. New York City, NY.

Website by

© 2024 Carmen Cicero. All Rights Reserved. New York City, NY.

Website by

The contents of this site, including all images and text, are for educational and non-commercial use only and are the sole property of Carmen Cicero. The contents of this site may not be reproduced in any form without written permission from Carmen Cicero. For all image requests and reproduction rights, please contact junekellygallery@earthlink.net.

© 2024 Carmen Cicero. All Rights Reserved. New York City, NY.

Website by