Carmen Cicero in Conversation

Carmen Cicero in Conversation

Carmen Cicero

“I resented Picasso, when I first went to college. I thought that he was a charlatan. But when I first saw the works that Picasso did when he was a very young man, I was stunned.”

David Ebony What was your first awareness of art—of fine art painting and drawing? What was your introduction to art history?

Carmen Cicero When I got out of the army, under the G.I. Bill, I could go to any school I chose. I didn’t know what the hell I was doing. I was mixed up. I thought I’d go to the nearest college to where I lived, which was [New Jersey] State Teachers College. Just as luck would have it, there were excellent teachers there. It was a small school, and I loved small schools because you knew everybody, and it was very comfortable. I found out the difference between what I thought art was, and how really vast and profound art really is. I knew little or nothing about art history. From the courses I took there, I learned a great deal about it. And there was another way I learned a lot about art and art history. I got a Guggenheim Fellowship grant for travel. When I made my itinerary, I just got a pencil and circled all the places with great museums, from England to Spain, and I loved every minute of that trip. I didn’t get tired of museums. I saw great art, and my knowledge of history grew from that more than anything else.

Ebony Was there a type of art or a period that you were most interested in? Or were there certain artists that you sought out?

Cicero No. At that time, I admired every artist whose works I saw in the museums.

Ebony Do you think it’s important for artists to know art history well, and if so, why?

Cicero Yes, I do. When people evaluate civilization, they talk about the arts and the sciences, and how significant these things are for any given situation in the course of the history of the world. An artist can then get an idea of where he or she stands within that history, the history of art. They can also better define what art is.

Ebony Could you name three artists who have influenced you, or inspired you the most over the years, and why?

Cicero Well, I have to say Pablo Picasso. I resented Picasso at first, when I first went to college. I thought that he was a charlatan. But when I first saw the works that Picasso did when he was a very young man, I was stunned. I thought that if this man could do this kind of work, almost like Renaissance painting, then what he did later has to have some great significance. That is how I first got involved with Picasso’s work. Another would be Robert Motherwell. I did some graduate work with Motherwell at Hunter College in New York, and it was right in the middle of the Abstract Expressionist period. I gravitated toward Abstract Expressionism right away. I instantly understood what it was all about. The first painting I ever sold was an Abstract Expressionist work, to the Newark Museum of Art.

Carmen Cicero

“I resented Picasso, when I first went to college. I thought that he was a charlatan. But when I first saw the works that Picasso did when he was a very young man, I was stunned.”

David Ebony What was your first awareness of art—of fine art painting and drawing? What was your introduction to art history?

Carmen Cicero When I got out of the army, under the G.I. Bill, I could go to any school I chose. I didn’t know what the hell I was doing. I was mixed up. I thought I’d go to the nearest college to where I lived, which was [New Jersey] State Teachers College. Just as luck would have it, there were excellent teachers there. It was a small school, and I loved small schools because you knew everybody, and it was very comfortable. I found out the difference between what I thought art was, and how really vast and profound art really is. I knew little or nothing about art history. From the courses I took there, I learned a great deal about it. And there was another way I learned a lot about art and art history. I got a Guggenheim Fellowship grant for travel. When I made my itinerary, I just got a pencil and circled all the places with great museums, from England to Spain, and I loved every minute of that trip. I didn’t get tired of museums. I saw great art, and my knowledge of history grew from that more than anything else.

Ebony Was there a type of art or a period that you were most interested in? Or were there certain artists that you sought out?

Cicero No. At that time, I admired every artist whose works I saw in the museums.

Ebony Do you think it’s important for artists to know art history well, and if so, why?

Cicero Yes, I do. When people evaluate civilization, they talk about the arts and the sciences, and how significant these things are for any given situation in the course of the history of the world. An artist can then get an idea of where he or she stands within that history, the history of art. They can also better define what art is.

Ebony Could you name three artists who have influenced you, or inspired you the most over the years, and why?

Cicero Well, I have to say Pablo Picasso. I resented Picasso at first, when I first went to college. I thought that he was a charlatan. But when I first saw the works that Picasso did when he was a very young man, I was stunned. I thought that if this man could do this kind of work, almost like Renaissance painting, then what he did later has to have some great significance. That is how I first got involved with Picasso’s work. Another would be Robert Motherwell. I did some graduate work with Motherwell at Hunter College in New York, and it was right in the middle of the Abstract Expressionist period. I gravitated toward Abstract Expressionism right away. I instantly understood what it was all about. The first painting I ever sold was an Abstract Expressionist work, to the Newark Museum of Art.

Carmen Cicero and Motherwell, ca 1990

“I remember Motherwell saying something along those lines, “A bad painting is your worst enemy.” I have come to believe that to be true.”

Ebony What about artists further back in history?

Cicero I liked the work of Albert Pinkham Ryder very much. He was able to create a very quiet spell with his paintings. His paintings are intimate and beautiful. They convey a still atmosphere that is quite remarkable—and magical.

Ebony What were the attributes of abstraction that most attracted you then? And what are the qualities of abstraction that have carried over to your more recent figurative images?

Cicero I went to abstract painting with great enthusiasm. And I have to say that what appealed to me was connected to my being a jazz musician. A jazz musician improvises in a very spontaneous way, in the moment. And with abstract painting, Abstract Expressionist painting in particular, the improvisational gestures of the brush and the improvisational aspect of jazz are very similar. For the musician, there are the chords and the melody, as a starting point, and for the painter, it’s the brushes and color that produce a visual experience, not unlike the sound experience that you can achieve with spontaneity in jazz.

Ebony What do you think is the relationship of music and art that is specific to your work?

Cicero I studied with the best music teachers in New York, and when I made my recordings, I played with top-flight musicians. I was a serious musician. When I was first asked if there was a relationship to music and painting, I would say, “No.” Music is music and painting is painting. But now I have a different attitude about that. I see that there is a very powerful connection with all of the arts—music, painting, dance. It is very hard to describe, but there is something that all great art produces. It’s difficult to define, but it’s an emotion, a feeling. There is a commonality in the arts, and hard to characterize, but it puts you in a timeless zone. It’s what one loves about the arts.

Ebony Your works on paper are either intensely colorful—the watercolors and collages—or stark black-and-white pencil and ink drawings. What are the pros and cons of color, and what is the case for black and white?

Cicero When you are composing with color, you work with a very specific element in art. Artists have made works with color alone, especially abstract paintings, for a long time. It is very difficult to organize color in a way that produces a significant work of art. When you are working with black and white—pencil or ink on paper—it is not as complex. And your attitude is different working with black and white. You can be more spontaneous. You’re willing to take a lot more chances because you’re working with fewer elements. If you make a mistake, it’s not as significant as if you were working with multicolor paints. Color is a much more complicated issue, and there are greater challenges. You don’t want to be too fanciful or overly improvisational.

Ebony Do you ever destroy your work? Is there ever a moment when you think it’s just not right? And when is that moment?

Cicero Yes. That moment is when you look at the work and you say to yourself, “This does not meet the standards of what I consider significant for myself.” If I feel that it doesn’t reach that standard, then I don’t want anyone else to see the work. It is a dangerous thing, though, to spontaneously tear up a work at the moment that you complete it. Periodically, I’ll go through my work, and there might be a questionable piece, but more often over the years, I’m glad that I saved it. So I wait a reasonable amount of time and then I clean house. I remember Motherwell saying something along those lines, “A bad painting is your worst enemy.” “I have come to believe that to be true.

Carmen Cicero and Motherwell, ca 1990

“I remember Motherwell saying something along those lines, “A bad painting is your worst enemy.” I have come to believe that to be true.”

Ebony What about artists further back in history?

Cicero I liked the work of Albert Pinkham Ryder very much. He was able to create a very quiet spell with his paintings. His paintings are intimate and beautiful. They convey a still atmosphere that is quite remarkable—and magical.

Ebony What were the attributes of abstraction that most attracted you then? And what are the qualities of abstraction that have carried over to your more recent figurative images?

Cicero I went to abstract painting with great enthusiasm. And I have to say that what appealed to me was connected to my being a jazz musician. A jazz musician improvises in a very spontaneous way, in the moment. And with abstract painting, Abstract Expressionist painting in particular, the improvisational gestures of the brush and the improvisational aspect of jazz are very similar. For the musician, there are the chords and the melody, as a starting point, and for the painter, it’s the brushes and color that produce a visual experience, not unlike the sound experience that you can achieve with spontaneity in jazz.

Ebony What do you think is the relationship of music and art that is specific to your work?

Cicero I studied with the best music teachers in New York, and when I made my recordings, I played with top-flight musicians. I was a serious musician. When I was first asked if there was a relationship to music and painting, I would say, “No.” Music is music and painting is painting. But now I have a different attitude about that. I see that there is a very powerful connection with all of the arts—music, painting, dance. It is very hard to describe, but there is something that all great art produces. It’s difficult to define, but it’s an emotion, a feeling. There is a commonality in the arts, and hard to characterize, but it puts you in a timeless zone. It’s what one loves about the arts.

Ebony Your works on paper are either intensely colorful—the watercolors and collages—or stark black-and-white pencil and ink drawings. What are the pros and cons of color, and what is the case for black and white?

Cicero When you are composing with color, you work with a very specific element in art. Artists have made works with color alone, especially abstract paintings, for a long time. It is very difficult to organize color in a way that produces a significant work of art. When you are working with black and white—pencil or ink on paper—it is not as complex. And your attitude is different working with black and white. You can be more spontaneous. You’re willing to take a lot more chances because you’re working with fewer elements. If you make a mistake, it’s not as significant as if you were working with multicolor paints. Color is a much more complicated issue, and there are greater challenges. You don’t want to be too fanciful or overly improvisational.

Ebony Do you ever destroy your work? Is there ever a moment when you think it’s just not right? And when is that moment?

Cicero Yes. That moment is when you look at the work and you say to yourself, “This does not meet the standards of what I consider significant for myself.” If I feel that it doesn’t reach that standard, then I don’t want anyone else to see the work. It is a dangerous thing, though, to spontaneously tear up a work at the moment that you complete it. Periodically, I’ll go through my work, and there might be a questionable piece, but more often over the years, I’m glad that I saved it. So I wait a reasonable amount of time and then I clean house. I remember Motherwell saying something along those lines, “A bad painting is your worst enemy.” “I have come to believe that to be true.

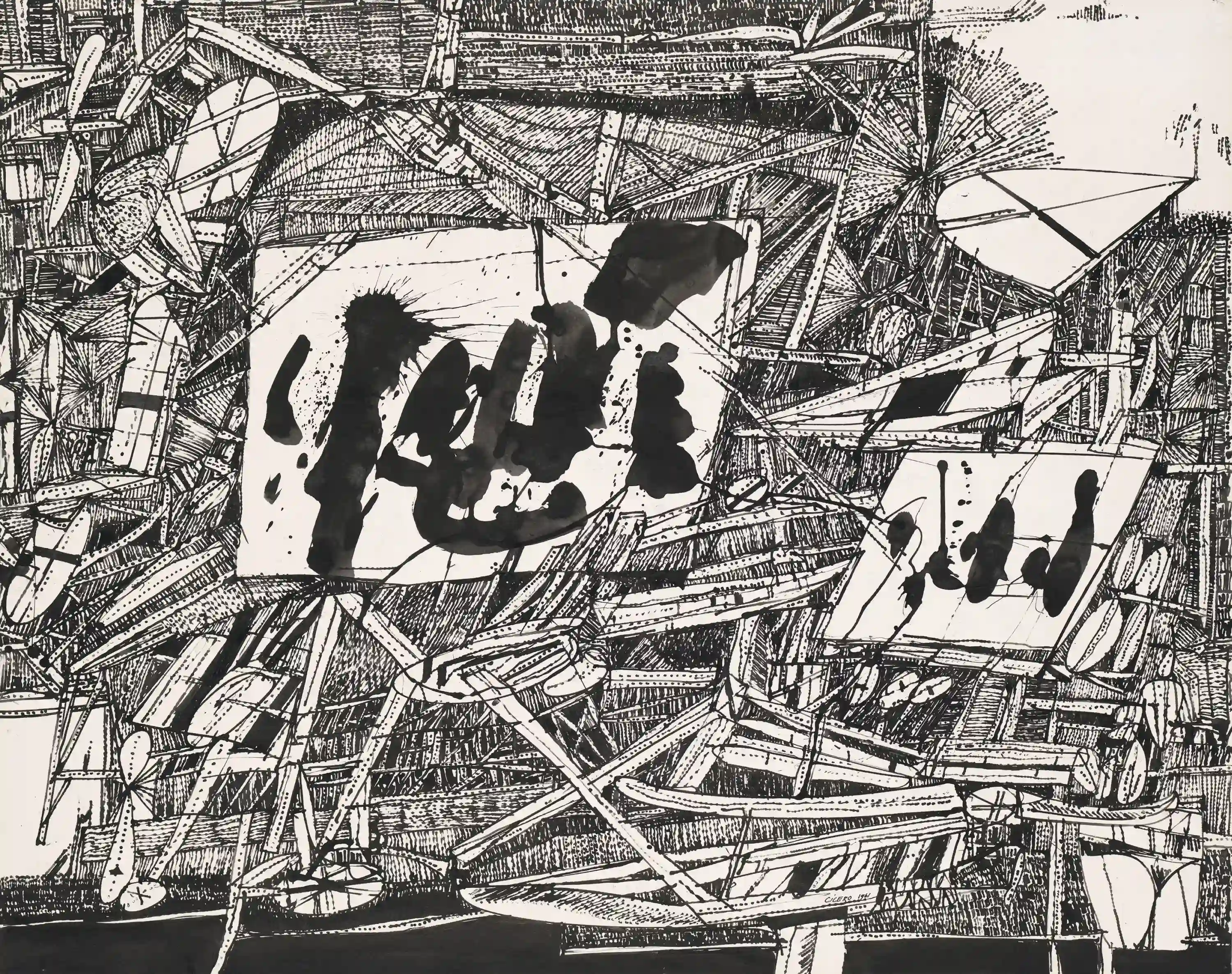

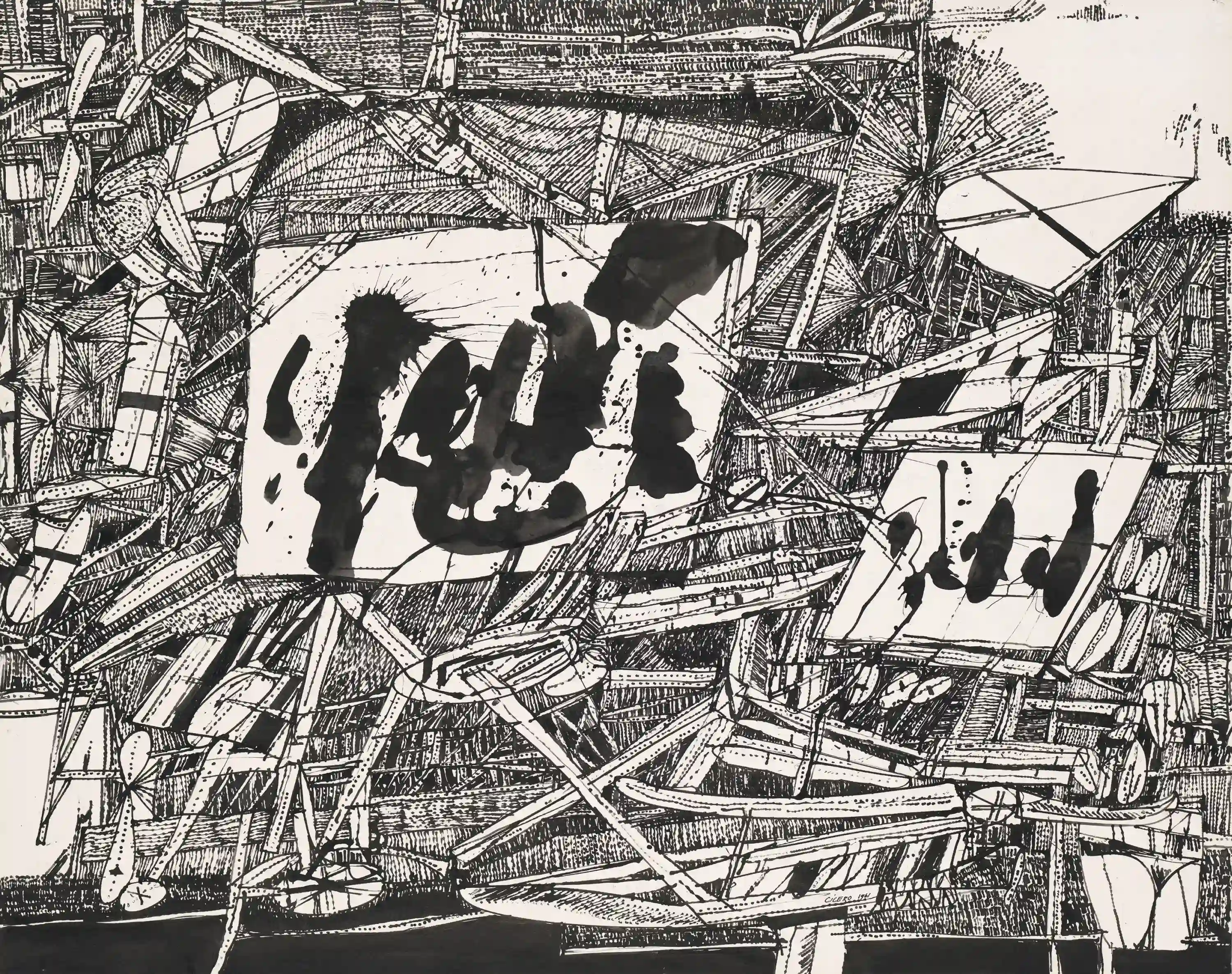

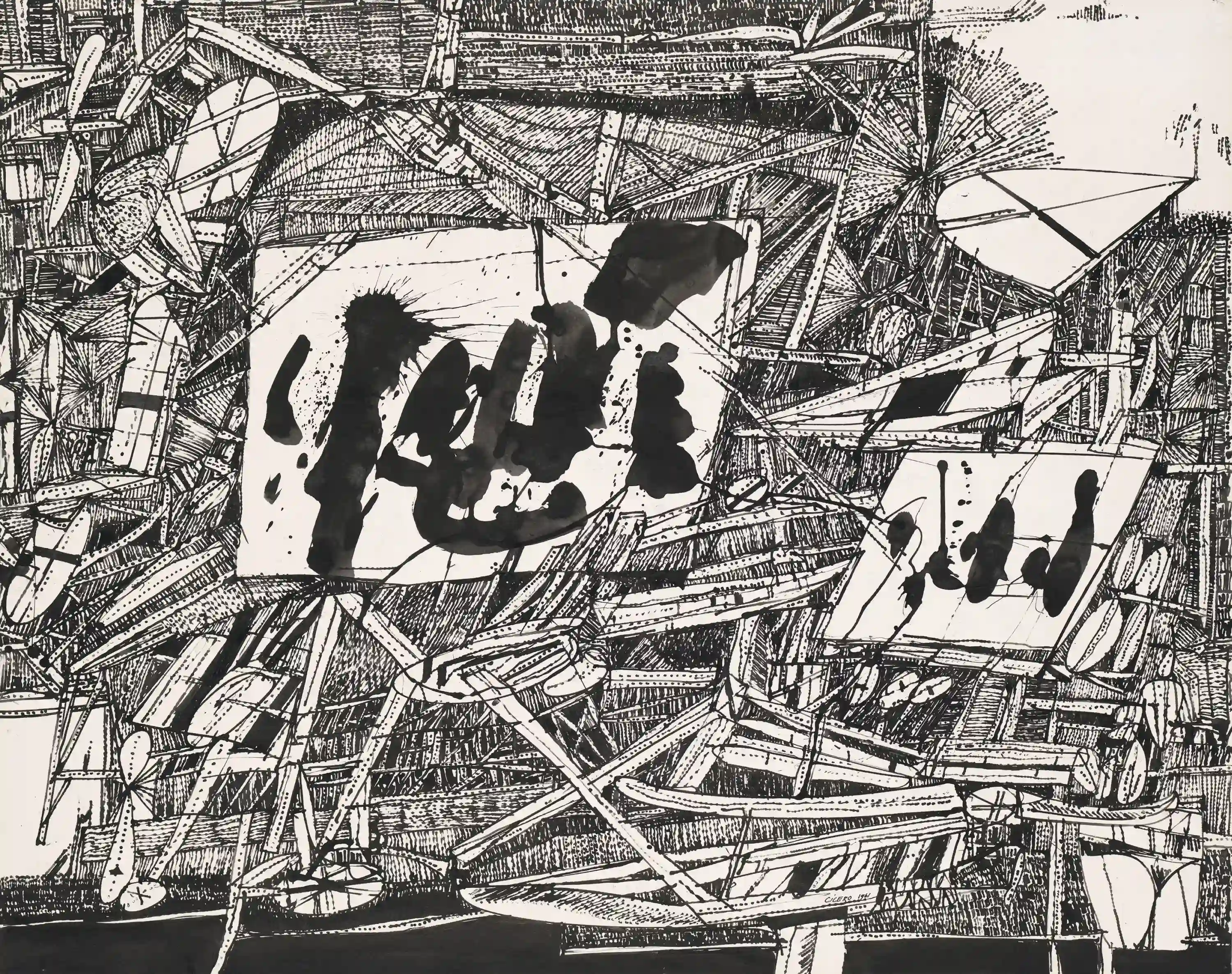

Farewell Abstract Expressionism, 1961. Ink on paper, 22-1/2 x 28-1/2 inches. Whitney Museum of American Art; gift of the Ford Foundation Purchase Program.

“I was in that show, along with Picasso, Miró, and pretty much all the great artists of the Western world at that time. I was pretty proud of myself, but for some reason I didn’t show up at the opening, and I don’t remember why.”

Ebony How did you recover from that?

Cicero I just made up my mind, and said, “Damn it, I am going to get through this, and I am going to continue to paint.” I think that painting pulled me through. I moved to New York. When I came to the city, and said I was an artist, everyone would ask, “Well, where is your work?” And I said, “I don’t have any.” I had a hell of time getting started again, but I did it.

Ebony What advice today would you give to young artists?

Cicero I would say, “Don’t do it!”

Ebony There is some hope out there, though, isn’t there?

Cicero When I entered the art scene in New York City as a young man, there were probably ten or fifteen galleries showing modern or contemporary art. Everybody knew everybody. When Willem de Kooning or Jackson Pollock had an opening, everyone would show up. The art world was small and exciting, and the international scene had just shifted from Paris to New York. There was a good chance for success. I just got a pamphlet the other day listing one hundred and fifty galleries in Lower Manhattan alone. A complete guide to all the New York galleries is like a telephone book. That’s what young people have to face when they go into it. So, when I say to young artists, “Don’t do it,” what I mean is, don’t do it unless you believe in your talent, you have great drive, and you can’t think of anything else you can do. If you love art, and you love what you do, it can be wonderful. You can have a charmed life. I feel like I have a charmed life.

©David Ebony 2024

Ebony How did you recover from that?

Cicero I just made up my mind, and said, “Damn it, I am going to get through this, and I am going to continue to paint.” I think that painting pulled me through. I moved to New York. When I came to the city, and said I was an artist, everyone would ask, “Well, where is your work?” And I said, “I don’t have any.” I had a hell of time getting started again, but I did it.

Ebony What advice today would you give to young artists?

Cicero I would say, “Don’t do it!”

Ebony There is some hope out there, though, isn’t there?

Cicero When I entered the art scene in New York City as a young man, there were probably ten or fifteen galleries showing modern or contemporary art. Everybody knew everybody. When Willem de Kooning or Jackson Pollock had an opening, everyone would show up. The art world was small and exciting, and the international scene had just shifted from Paris to New York. There was a good chance for success. I just got a pamphlet the other day listing one hundred and fifty galleries in Lower Manhattan alone. A complete guide to all the New York galleries is like a telephone book. That’s what young people have to face when they go into it. So, when I say to young artists, “Don’t do it,” what I mean is, don’t do it unless you believe in your talent, you have great drive, and you can’t think of anything else you can do. If you love art, and you love what you do, it can be wonderful. You can have a charmed life. I feel like I have a charmed life.

©David Ebony 2024

Ebony Some observers find psychosexual narratives in some many of your images. Others suggest that there are sociopolitical themes in your work. How do you personally respond to the resultant narrative content of your images?

Cicero I rarely consciously put sexual imagery in my paintings. Although I do on occasion. The things that come from the unconscious, without intervention of the intellect, [are] likely to be valid as an expression. For me, whatever emerges as sexual content in that way is valid; and sex is, of course, just a part of life. Regarding the political, I hate political art. What I mean by political art is when someone puts forward ideas or political views in their works that are specific to the time and place they are living—communism, socialism, fascism, or even democracy and capitalism, framed as a significant social statement. An artist must remember that one hundred years from today, those things that you consider so important as political and social expression will probably be unknown, and almost certainly not understood. For example, who knows what the specific sociopolitical situation was at the time that Rembrandt painted? Or what were the prevailing political views of Van Gogh’s era? That is not what is important about their art. I believe that authoritarian regimes are those that use and value political art the most.

Ebony What is the role of humor in your art? And what are some incidents of humor you have found in other artist’s works?

Cicero When I was a young man, I was very funny. When you get to be my age, though, being a clown is unseemly. I enjoyed being funny, and making people laugh. And I do have a sense of humor in my art. But back then, comedy or even having a sense of humor in your work was very tricky; people frowned upon it. You see very little humor in work of the 1940s, ’50s, or even later. But more recently, I said, if that’s what I think and feel—and I think I’m pretty damn good—I don’t care any longer about who might like it or not like it. And if it doesn’t go anywhere, I don’t give a damn about that, either. There was some humor in the Dada period. Duchamp had humor. And in the past, Daumier had humor in his work. You know the bathtub image, with the guy just sinking into the tub? Some of Goya’s works also had humor in them. Many people think of his work as political. But I see it primarily as a comment on the human condition.

Ebony So far in your long career, what would you say was the highest point, and what was the lowest?

Cicero I think the highest point was the first show at the Guggenheim Museum [in 1959] that Frank Lloyd Wright had designed. I was in that show, along with Picasso, Miró, and pretty much all the great artists of the Western world at that time. I was pretty proud of myself, but for some reason I didn’t show up at the opening, and I don’t remember why. That’s the exhibition where Miró saw and admired my work. The lowest point, without a doubt, was when my carriage house in Englewood, New Jersey, burned to the ground. The top floor was my apartment, and the first floor was my studio. It was filled with my paintings, which were figurative abstractions. No one was painting like that at the time. Some artists would come by and ridicule them. But as far as I know, I was one of the first Figurative Expressionists. Everything was lost in the fire.

Ebony So then it appeared as if you had abruptly changed your style, but the transitional works were there, correct?

Cicero I made a drawing, Farewell Abstract Expressionism [1961], that the Whitney Museum owns, that relates to the transition. But there were major canvases in the studio, paintings fifteen feet long, and many other works of all kinds that are gone. I remember one painting called The Cancer. My father died of cancer, and soon after, I made this painting that was grim and deeply emotional. It showed a man with his legs cut off, and grimacing. I didn’t know it at the time, but my father had testicular cancer and they had to remove them. The image outdid Francis Bacon in terms of grimness. But I think it was a very good painting—filled with emotion and intensity.

Ebony Did you keep photographic records of them?

Cicero Yes! But those burned, too.

Ebony How did you recover from that?

Cicero I just made up my mind, and said, “Damn it, I am going to get through this, and I am going to continue to paint.” I think that painting pulled me through. I moved to New York. When I came to the city, and said I was an artist, everyone would ask, “Well, where is your work?” And I said, “I don’t have any.” I had a hell of time getting started again, but I did it.

Ebony What advice today would you give to young artists?

Cicero I would say, “Don’t do it!”

Ebony There is some hope out there, though, isn’t there?

Cicero When I entered the art scene in New York City as a young man, there were probably ten or fifteen galleries showing modern or contemporary art. Everybody knew everybody. When Willem de Kooning or Jackson Pollock had an opening, everyone would show up. The art world was small and exciting, and the international scene had just shifted from Paris to New York. There was a good chance for success. I just got a pamphlet the other day listing one hundred and fifty galleries in Lower Manhattan alone. A complete guide to all the New York galleries is like a telephone book. That’s what young people have to face when they go into it. So, when I say to young artists, “Don’t do it,” what I mean is, don’t do it unless you believe in your talent, you have great drive, and you can’t think of anything else you can do. If you love art, and you love what you do, it can be wonderful. You can have a charmed life. I feel like I have a charmed life.

©David Ebony 2024

Ebony Some observers find psychosexual narratives in some many of your images. Others suggest that there are sociopolitical themes in your work. How do you personally respond to the resultant narrative content of your images?

Cicero I rarely consciously put sexual imagery in my paintings. Although I do on occasion. The things that come from the unconscious, without intervention of the intellect, [are] likely to be valid as an expression. For me, whatever emerges as sexual content in that way is valid; and sex is, of course, just a part of life. Regarding the political, I hate political art. What I mean by political art is when someone puts forward ideas or political views in their works that are specific to the time and place they are living—communism, socialism, fascism, or even democracy and capitalism, framed as a significant social statement. An artist must remember that one hundred years from today, those things that you consider so important as political and social expression will probably be unknown, and almost certainly not understood. For example, who knows what the specific sociopolitical situation was at the time that Rembrandt painted? Or what were the prevailing political views of Van Gogh’s era? That is not what is important about their art. I believe that authoritarian regimes are those that use and value political art the most.

Ebony What is the role of humor in your art? And what are some incidents of humor you have found in other artist’s works?

Cicero When I was a young man, I was very funny. When you get to be my age, though, being a clown is unseemly. I enjoyed being funny, and making people laugh. And I do have a sense of humor in my art. But back then, comedy or even having a sense of humor in your work was very tricky; people frowned upon it. You see very little humor in work of the 1940s, ’50s, or even later. But more recently, I said, if that’s what I think and feel—and I think I’m pretty damn good—I don’t care any longer about who might like it or not like it. And if it doesn’t go anywhere, I don’t give a damn about that, either. There was some humor in the Dada period. Duchamp had humor. And in the past, Daumier had humor in his work. You know the bathtub image, with the guy just sinking into the tub? Some of Goya’s works also had humor in them. Many people think of his work as political. But I see it primarily as a comment on the human condition.

Ebony So far in your long career, what would you say was the highest point, and what was the lowest?

Cicero I think the highest point was the first show at the Guggenheim Museum [in 1959] that Frank Lloyd Wright had designed. I was in that show, along with Picasso, Miró, and pretty much all the great artists of the Western world at that time. I was pretty proud of myself, but for some reason I didn’t show up at the opening, and I don’t remember why. That’s the exhibition where Miró saw and admired my work. The lowest point, without a doubt, was when my carriage house in Englewood, New Jersey, burned to the ground. The top floor was my apartment, and the first floor was my studio. It was filled with my paintings, which were figurative abstractions. No one was painting like that at the time. Some artists would come by and ridicule them. But as far as I know, I was one of the first Figurative Expressionists. Everything was lost in the fire.

Ebony So then it appeared as if you had abruptly changed your style, but the transitional works were there, correct?

Cicero I made a drawing, Farewell Abstract Expressionism [1961], that the Whitney Museum owns, that relates to the transition. But there were major canvases in the studio, paintings fifteen feet long, and many other works of all kinds that are gone. I remember one painting called The Cancer. My father died of cancer, and soon after, I made this painting that was grim and deeply emotional. It showed a man with his legs cut off, and grimacing. I didn’t know it at the time, but my father had testicular cancer and they had to remove them. The image outdid Francis Bacon in terms of grimness. But I think it was a very good painting—filled with emotion and intensity.

Ebony Did you keep photographic records of them?

Cicero Yes! But those burned, too.

Farewell Abstract Expressionism, 1961. Ink on paper, 22-1/2 x 28-1/2 inches. Whitney Museum of American Art; gift of the Ford Foundation Purchase Program.

“I was in that show, along with Picasso, Miró, and pretty much all the great artists of the Western world at that time. I was pretty proud of myself, but for some reason I didn’t show up at the opening, and I don’t remember why.”

Ebony How did you recover from that?

Cicero I just made up my mind, and said, “Damn it, I am going to get through this, and I am going to continue to paint.” I think that painting pulled me through. I moved to New York. When I came to the city, and said I was an artist, everyone would ask, “Well, where is your work?” And I said, “I don’t have any.” I had a hell of time getting started again, but I did it.

Ebony What advice today would you give to young artists?

Cicero I would say, “Don’t do it!”

Ebony There is some hope out there, though, isn’t there?

Cicero When I entered the art scene in New York City as a young man, there were probably ten or fifteen galleries showing modern or contemporary art. Everybody knew everybody. When Willem de Kooning or Jackson Pollock had an opening, everyone would show up. The art world was small and exciting, and the international scene had just shifted from Paris to New York. There was a good chance for success. I just got a pamphlet the other day listing one hundred and fifty galleries in Lower Manhattan alone. A complete guide to all the New York galleries is like a telephone book. That’s what young people have to face when they go into it. So, when I say to young artists, “Don’t do it,” what I mean is, don’t do it unless you believe in your talent, you have great drive, and you can’t think of anything else you can do. If you love art, and you love what you do, it can be wonderful. You can have a charmed life. I feel like I have a charmed life.

©David Ebony 2024

Ebony How did you recover from that?

Cicero I just made up my mind, and said, “Damn it, I am going to get through this, and I am going to continue to paint.” I think that painting pulled me through. I moved to New York. When I came to the city, and said I was an artist, everyone would ask, “Well, where is your work?” And I said, “I don’t have any.” I had a hell of time getting started again, but I did it.

Ebony What advice today would you give to young artists?

Cicero I would say, “Don’t do it!”

Ebony There is some hope out there, though, isn’t there?

Cicero When I entered the art scene in New York City as a young man, there were probably ten or fifteen galleries showing modern or contemporary art. Everybody knew everybody. When Willem de Kooning or Jackson Pollock had an opening, everyone would show up. The art world was small and exciting, and the international scene had just shifted from Paris to New York. There was a good chance for success. I just got a pamphlet the other day listing one hundred and fifty galleries in Lower Manhattan alone. A complete guide to all the New York galleries is like a telephone book. That’s what young people have to face when they go into it. So, when I say to young artists, “Don’t do it,” what I mean is, don’t do it unless you believe in your talent, you have great drive, and you can’t think of anything else you can do. If you love art, and you love what you do, it can be wonderful. You can have a charmed life. I feel like I have a charmed life.

©David Ebony 2024

Ebony Some observers find psychosexual narratives in some many of your images. Others suggest that there are sociopolitical themes in your work. How do you personally respond to the resultant narrative content of your images?

Cicero I rarely consciously put sexual imagery in my paintings. Although I do on occasion. The things that come from the unconscious, without intervention of the intellect, [are] likely to be valid as an expression. For me, whatever emerges as sexual content in that way is valid; and sex is, of course, just a part of life. Regarding the political, I hate political art. What I mean by political art is when someone puts forward ideas or political views in their works that are specific to the time and place they are living—communism, socialism, fascism, or even democracy and capitalism, framed as a significant social statement. An artist must remember that one hundred years from today, those things that you consider so important as political and social expression will probably be unknown, and almost certainly not understood. For example, who knows what the specific sociopolitical situation was at the time that Rembrandt painted? Or what were the prevailing political views of Van Gogh’s era? That is not what is important about their art. I believe that authoritarian regimes are those that use and value political art the most.

Ebony What is the role of humor in your art? And what are some incidents of humor you have found in other artist’s works?

Cicero When I was a young man, I was very funny. When you get to be my age, though, being a clown is unseemly. I enjoyed being funny, and making people laugh. And I do have a sense of humor in my art. But back then, comedy or even having a sense of humor in your work was very tricky; people frowned upon it. You see very little humor in work of the 1940s, ’50s, or even later. But more recently, I said, if that’s what I think and feel—and I think I’m pretty damn good—I don’t care any longer about who might like it or not like it. And if it doesn’t go anywhere, I don’t give a damn about that, either. There was some humor in the Dada period. Duchamp had humor. And in the past, Daumier had humor in his work. You know the bathtub image, with the guy just sinking into the tub? Some of Goya’s works also had humor in them. Many people think of his work as political. But I see it primarily as a comment on the human condition.

Ebony So far in your long career, what would you say was the highest point, and what was the lowest?

Cicero I think the highest point was the first show at the Guggenheim Museum [in 1959] that Frank Lloyd Wright had designed. I was in that show, along with Picasso, Miró, and pretty much all the great artists of the Western world at that time. I was pretty proud of myself, but for some reason I didn’t show up at the opening, and I don’t remember why. That’s the exhibition where Miró saw and admired my work. The lowest point, without a doubt, was when my carriage house in Englewood, New Jersey, burned to the ground. The top floor was my apartment, and the first floor was my studio. It was filled with my paintings, which were figurative abstractions. No one was painting like that at the time. Some artists would come by and ridicule them. But as far as I know, I was one of the first Figurative Expressionists. Everything was lost in the fire.

Ebony So then it appeared as if you had abruptly changed your style, but the transitional works were there, correct?

Cicero I made a drawing, Farewell Abstract Expressionism [1961], that the Whitney Museum owns, that relates to the transition. But there were major canvases in the studio, paintings fifteen feet long, and many other works of all kinds that are gone. I remember one painting called The Cancer. My father died of cancer, and soon after, I made this painting that was grim and deeply emotional. It showed a man with his legs cut off, and grimacing. I didn’t know it at the time, but my father had testicular cancer and they had to remove them. The image outdid Francis Bacon in terms of grimness. But I think it was a very good painting—filled with emotion and intensity.

Ebony Did you keep photographic records of them?

Cicero Yes! But those burned, too.

The contents of this site, including all images and text, are for educational and non-commercial use only and are the sole property of Carmen Cicero. The contents of this site may not be reproduced in any form without written permission from Carmen Cicero. For all image requests and reproduction rights, please contact junekellygallery@earthlink.net.

© 2024 Carmen Cicero. All Rights Reserved. New York City, NY.

Website by

© 2024 Carmen Cicero. All Rights Reserved. New York City, NY.

Website by

The contents of this site, including all images and text, are for educational and non-commercial use only and are the sole property of Carmen Cicero. The contents of this site may not be reproduced in any form without written permission from Carmen Cicero. For all image requests and reproduction rights, please contact junekellygallery@earthlink.net.

© 2024 Carmen Cicero. All Rights Reserved. New York City, NY.

Website by